The Birth of Fiat Money34 minuti

- Introduction: understanding economy and history

- Deflation and prosperity

- When fiat money started

- When deflation hurts

- The distorsions of the bimetallic regime

- The “crime” of 1873

- The State creator of bubbles

- The spiral of the omnipotent State

- The mishaps of State remedy

- The dangerous contradiction of anti-capitalism

- Technological progress and unemployment

- The gold standard and the Wizard of Oz

- The “market” crisis justifying the emergence of central banking

- The 1907 panic between speculation, regulation and antitrust

- Bank bailouts

- Tragic ending

- Bitcoin the solution

Fiat Currency, Overproduction Crises, Strikes, Socialism, State Intervention, and Monetary Policies: All of these phenomena originated during a dense period in the history of civilization. Understanding that historical period means understanding modern economics and the role of currency, interpreting what is happening today, and imagining what will happen in the future. A good theoretical preparation on these issues also guarantees the best arguments in favor of revolutionary solutions such as Bitcoin.

In the two decades from 1870 to 1890, many Western countries transitioned from bimetallism to the gold standard, and it was during these years that states began to play a more active role in monetary policy, particularly in response to the first economic “crises” of overproduction in history, such as the Panic of 1873 in the United States[1].

Between 1871 and 1873, Marx’s Manifesto was published in six languages, and in 1872 it arrived in the United States, where the first nationwide strikes (the Great Railroad Strike) took place in 1877. With reference to the economic situation of this two-decade period, Irving Fisher developed the first economic theories that attributed the blame for the crisis to deflation, giving rise to a myth, that of low and stable inflation, which is still professed today. In the same period, the concept of “fiat currency” was also born, when the term came up in 1878 at a party meeting in the United States. In 1874, President Grant vetoed the Inflation bill promoted by Congress, which called for the printing of $100 million in banknotes. The first antitrust laws were enacted in the United States in 1890 (the Sherman Antitrust Act). In general, dirigiste and interventionist theories began to take hold in these years, destined to dominate the political landscape of the 20th century with Keynes. But on the other side of the barricade, Carl Menger, who published his works precisely between 1871 and 1892, laid the foundations of the Austrian School of economics in support of laissez-faire.

In this article, we will try to explain why, at a certain historical moment, it was deemed necessary for public authority to intervene in the monetary economy. Studying a given phenomenon in the first cases in which it appeared allows us to visualize it in its most genuine and understandable form. Therefore, we focus here on this era, when economic and social structures were still relatively simple compared to today, and therefore easier to analyze. We will mainly focus our analysis on America and the dollar, due to the numerous historical data available and the historical influence and impact that the United States has had – and still has – on the rest of the world.

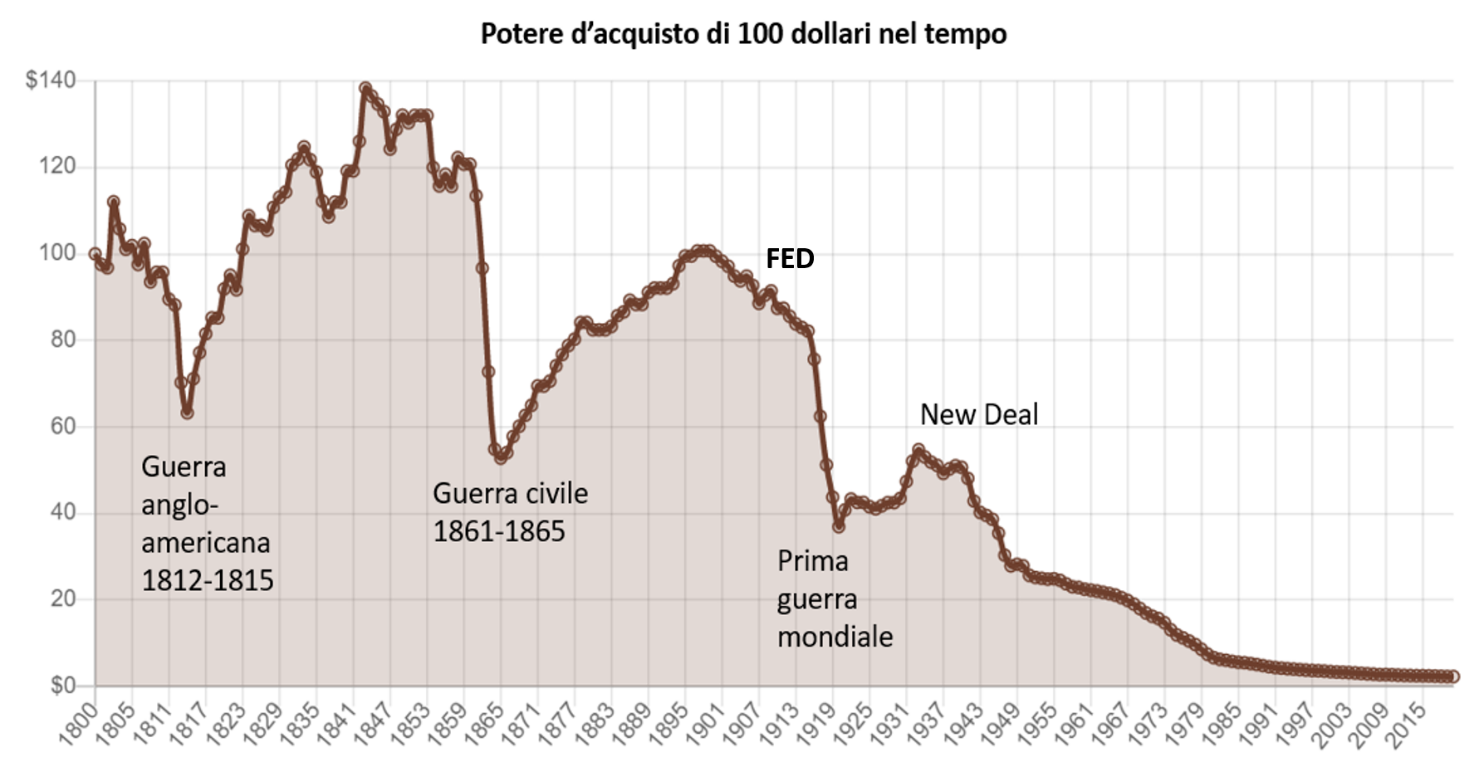

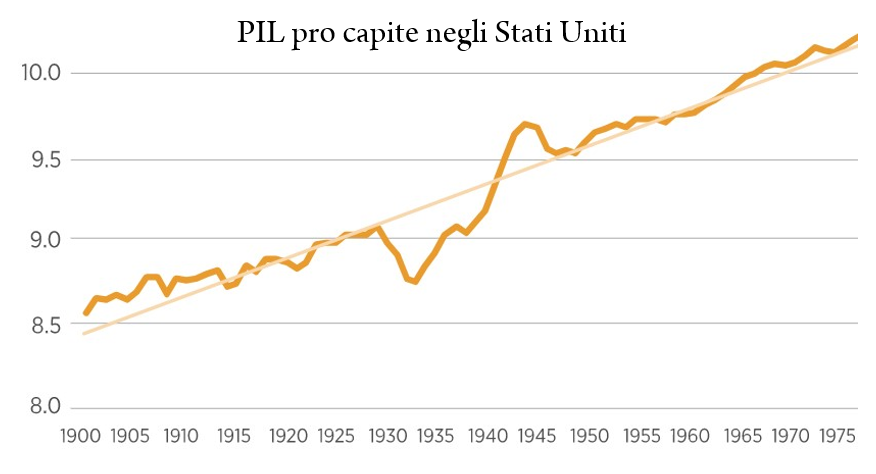

Before the 20th century, the only years in which the dollar saw substantial inflation were the Anglo-American War (1812-1815) and the Civil War (1861-1865). For the rest of the time, the dollar has always had a deflationary trend. Deflation marked an era of prosperity, wealth, trade, and great technological innovations, in which the United States became the world’s leading power, quintupling its GDP and surpassing the British Empire. Nowadays, Keynesian mystics tell us that an economy will thrive if low and constant inflation is maintained, despite any scientific, historical, or empirical argument. Today, it is enough to do a little shopping to realize that often the most prosperous and growing markets are deflationary ones, such as electronics and computing, where prices continue to fall despite an increase in the value (and performance) of the goods produced.

Despite the high growth of productivity and per capita GDP in the second half of the 19th century, there were still turbulent periods in the United States, with speculative bubbles and high unemployment. While unemployment has always been below 5% for the rest of the century, the rate rose between 1873 and 1880, and then again in 1892-1893, peaking at around 14%[2]. Today, the term Great Depression is associated with the 1929 crisis, but previously it referred to this late 19th-century period, now more commonly known as the “Long Depression.” Contrary to more recent major crises, it is inappropriate to speak of a depression in this case – as Rothbard already pointed out – given the constant per capita GDP growth throughout the period. The discomfort was generated exclusively by unemployment and therefore the precarious situation (even temporarily) of some segments of the population. Explaining the reason for these crises and the phenomenon of unemployment, which was virtually absent before the industrialized world, is important to clarify what the effects of state intervention in regulating the economy are.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), the United States began for the first time to print banknotes without underlying gold or silver. Citizens were already accustomed to using paper as currency, since banknotes had already been in circulation for some time. However, these were nothing more than bearer bonds issued by private banks, always redeemable in gold or silver at the bank that issued them. There were about 2000 private banks that printed “banknotes” in this way. The government had also already issued banknotes, convertible into metal if not immediately, at least at a certain date, thus always presenting an underlying guarantee. A private citizen could exchange their raw silver or gold for currency at the Treasury, and vice versa. With the Civil War, however, banknotes were printed for the first time, called “greenbacks”, based solely on “trust” in the “nation” (the Union led by Lincoln). The extraordinary measure was deemed necessary to finance the war against the Confederates, as simple taxation would not have been enough to cover the wartime effort.

The average citizen may not have perceived the historical weight of this initiative, and in fact the new fiat dollars were likely handled just like any preexisting banknote, without the perception that an epochal change in history was about to occur. However, the creators of the fiat money banknote were well aware of what they were doing. When they asked Lincoln whether to also include the motto “In God We Trust” on the banknotes, which was printed on metal coins, he ironically commented that if they had to give a label to the banknote, a biblical quote would have been more appropriate: “I don’t have any silver or gold! But I will give you what I do have”. In this way, 430 million dollars were printed, a huge amount considering that at the time there were only 207 million banknotes backed by gold and silver in circulation, in addition to 275 million metal coins.[3]. As a result, gold more than doubled in price against the dollar between 1861 and 1864.

Like any war, the American Civil War brought poverty and crisis. A few years later, in 1869, the dollar and the American economy still felt the effects of the war trauma, so President Grant began selling the gold that the Treasury Department held in reserve. His explicit intent was to restore the pre-war monetary system by withdrawing from circulation the cash previously issued without a metallic backing (the greenbacks), believing that inflationary policy was harmful to the economy. In March 1869, he approved the Public Credit Act, which treated greenbacks as state bonds redeemable in gold, effectively reintroducing the gold standard. Black Friday[4] is a holiday that specifically recalls the extraordinary fall in the price of gold that occurred in a few minutes on Friday, September 24, 1869, following the sale of gold by the Department of the Treasury (for $4 million)

Grant applied an effective remedy by restoring the gold standard, but not without consequences on the real economy. The instability of the monetary policy, with a period of high inflation (issuing greenbacks) followed by a period of strong deflation (withdrawing greenbacks) had a redistributive effect with distorting impacts on the real economy. In fact, if the Treasury sells gold in exchange for banknotes, it effectively “buys” dollars, destroying and removing them from circulation, thereby increasing the price of those remaining on the market.

By restricting the supply of dollars, the price of dollars relative to real goods such as iron, socks, and corn also increases. If the dollar appreciates, those who have borrowed in dollars must work and produce more to repay the debt. Let’s imagine the situation with a simple example: a farmer buys a piece of land for 100 dollars borrowed, knowing that the following year he can sell 100 ears of corn for 1 dollar each, thus earning 100 dollars and being able to repay the loan to the bank. However, if the price of the dollar rises relative to corn (deflation), the farmer will not be able to repay the debt: by selling 100 ears of corn, he could manage to scrape together, for example, 80 dollars instead of 100. When he took out the loan, during an inflationary period, the farmer imagined that the price of corn would rise relative to the dollar, not vice versa. Or, he did not imagine that the price ratio of dollars/corn could be conditioned by monetary policies, so he is surprised by government action without being able to calculate that variable in his entrepreneurial choices.

Deflation is not a problem in itself, it becomes so if it is not calculated in advance. The problem is all the more accentuated the more economic agents are accustomed to an inflationary regime and contract debts and credits accordingly.

Already in 1869, deflation was seen as a harm to farmers in the West[5]: Americans quickly realized that the government has redistributive power in the real economy through monetary management. The natural consequence is the formation of coalitions to lobby, as those who apply political pressure can obtain a distorting intervention of the natural market conditions, in their favor. This is why monetary policy has been a source of conflict between social parties and their respective representatives in Congress since then.

There was a party devoted to pursuing inflationary policies through printing banknotes: the Greenback Party. It was at a meeting of this party that the term “fiat money” came up in 1878. However, the danger of indiscriminate creation of banknotes without underlying assets was averted by Grant in 1874 when the president vetoed the Inflation Bill Act promoted by the Congress, which would have stopped the withdrawal of banknotes without underlying assets and allowed for the printing of another $100 million.

Despite Grant’s veto having taken a devastating weapon (fiat money) out of Congress’s hands, which would only reappear in the following century, the United States government had still had a considerable influence on monetary economics since 1792 (the first Coinage act), when the value of a dollar was based on a fixed amount of silver and, at the same time, also on a fixed amount of gold, thus determining a value ratio between the two metals.

Fixed exchange rates necessarily entail imbalances. If, for example, the price of silver depreciates relative to gold on the metals market (due to a natural variation in market supply and demand), those who own silver have an incentive to bring it to the State mint to have dollars coined, since the value in gold terms of those (silver) dollars, being fixed by law, is higher than the market price of the silver contained in them. So citizens are encouraged to bring their bullion to the mint, have more dollars printed, and thereby cause an increase in the money supply. In short, in the presence of fixed rates between gold and silver, a variation in the market prices of metals can cause inflation in the dollar.

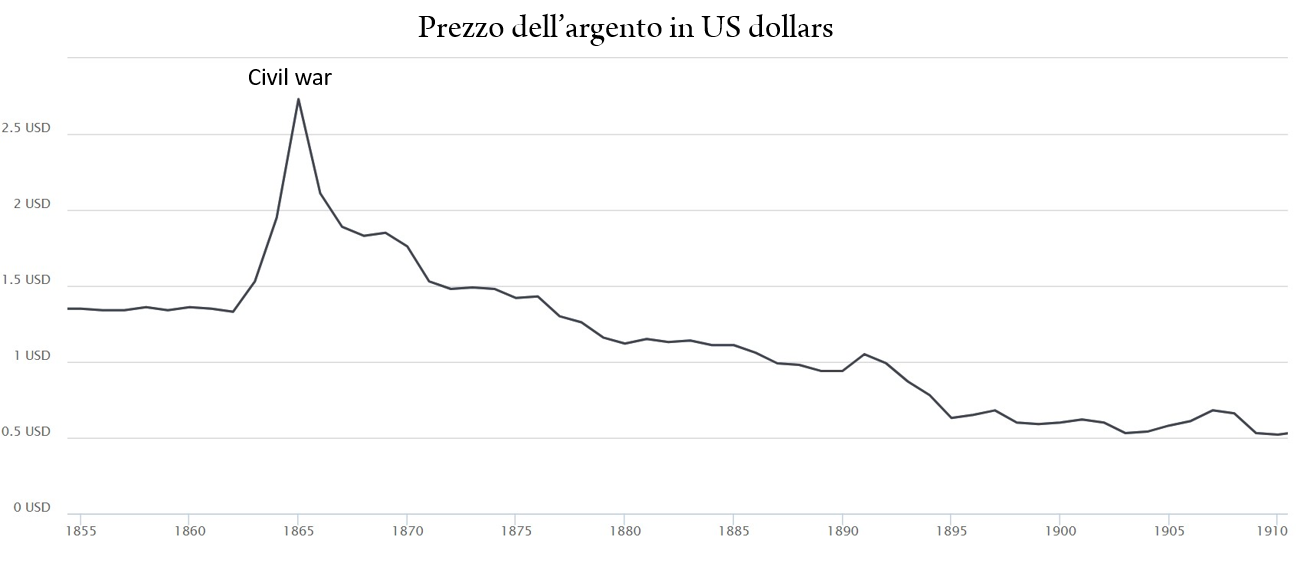

The slowness of communications, the backwardness of the production system, and the relative stability of prices in the metals market did not make the problem of fixed exchange rates perceptible for a long time, which instead arose in the second half of the nineteenth century, especially in periods when new deposits were found and prices underwent more abrupt changes. The gold rush that brought 300,000 people to California in the 1850s caused the price of gold to fall, while in the 1860s and 1870s, the discovery of silver deposits in Nevada (and the transition to the gold standard of the German Empire in 1871) caused the price of silver to plummet.

The price of silver gradually loses purchasing power due to the exploitation of new deposits. The previous surge was due to the Civil War, when, like gold, it was seen as a safe haven asset, in the face of inflation caused by the printing of greenbacks (graph source: denvergold.org).

Inflation and deflation of dollars thus depended on the monetary rules of Congress and had an impact on the value of debts and credits in the economy: western farmers were often indebted to banks in the east, so they benefited from greater inflation of the dollar because the real value of their debts (nominated in dollars) decreased, while they were disadvantaged by the deflation of the dollar, because in that case the value of their production relative to the dollar and therefore relative to the debts contracted decreased.

Given the devaluation of silver in relation to the fixed ratio with gold established by the State Mint, more and more silver was brought from the western mines to be minted into silver dollars. As a result, these coins ended up having a real value (the weight of the silver used to make the coin) lower than the nominal value written on the coin. If a coin has a nominal value higher than its real value, it is considered a “bad” coin and, in the presence of alternatives, the holder will want to get rid of it. According to Gresham’s law, the “bad” coin drives the “good” coin out of circulation, precisely because everyone intends to buy goods and services using only silver coins (which are “bad”) to pay for them, in order to get rid of them, while keeping gold dollars or raw gold in reserve.

Some government officials[6] already in the late 1860s feared that silver, precisely because of Gresham’s law, then well-known, could completely replace gold in common exchanges between citizens, jeopardizing the bimetallic regime in favor of a silver standard. Others, such as then Treasury Secretary George Boutwell, believed that the fate of the United States was the gold standard, like powers such as the British Empire and Germany. The result was that, albeit passing a bit quietly, among discussions of secondary clauses, Congress approved the Coinage Act of 1873, which prohibited the minting of new silver coins.

At first, the law did not cause particular uproar, also because from 1873 to 1876 the price of silver had remained rather stable, only in 1876 it dropped from 1.43 to 1.3 dollars, as a natural reaction to the increase in supply. At that point, those who owned silver bullion went to the State Mint to have dollars coined, only to discover that it was no longer possible due to the 1873 law. The effect was not welcomed by the western miners at all. Many lost their jobs because the extraction costs exceeded the profits from the sale of silver. Due to the deflationary effect caused by the halt in the minting of new dollars, the law also affected those farmers who had contracted debts to seek their fortune in the West, to the advantage of the banks in the East. The growth in the real value of debts, due to an unexpected deflation, combined with the drought of those years, caused many farmers to fail. It was shouted out as a scandal: the Coinage Act (or Mint Act) was called the “Crime of ’73“, and “Silverite” movements were born to pressure Congress to allow the free minting of silver coins.

Together with problems in the agricultural and mining sectors, the railway market bubble burst. The crisis was due to a previous period of speculative frenzy, which was not only driven by a natural market tendency towards excessive enthusiasm for an innovative and potentially very profitable sector. On the contrary, the state and monetary expansions (carried out by commercial banks) played a key role, for two reasons:

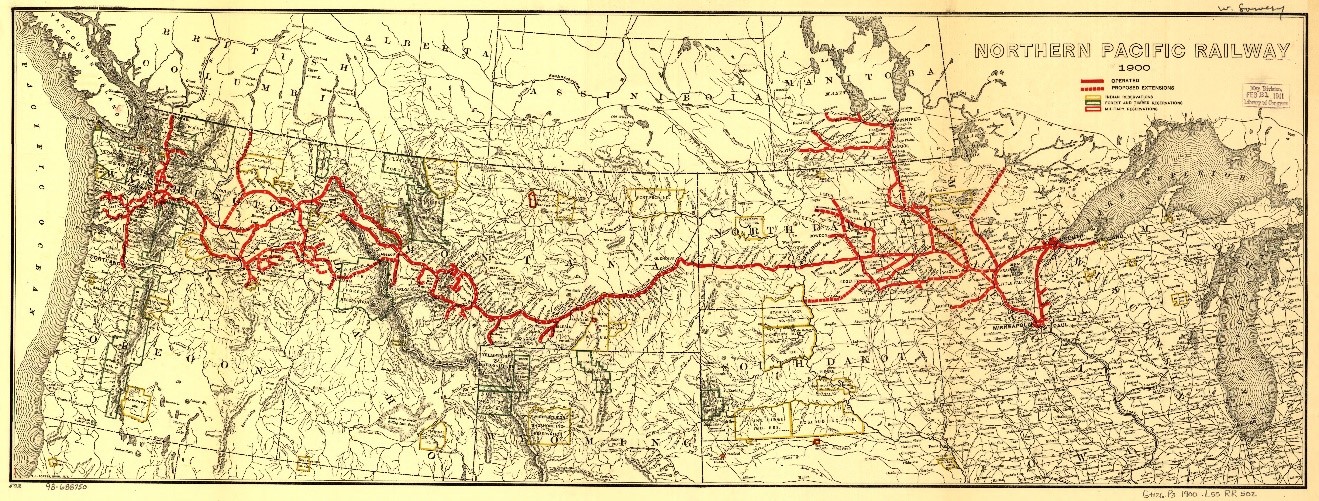

- Government subsidies: the government granted rights of way on land to build railways for 175 million acres, or one-tenth of the entire US territory; in addition, it flooded the market with liquidity, creating public debt specifically to finance railways (Congress had approved the Pacific Railway Act in 1862).

- Fractional reserve banking: many banks invested a disproportionate share of depositor funds in railways, thus using their clients’ money (through misappropriation due to fractional reserve banking) to finance risky speculative projects. The commercial banks that failed during this period were 5,000, as they no longer had enough metal in reserve to support deposit withdrawals. In particular, the failure of “Jay Cooke & Company” impacted the market due to its participation in the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway (over 10,000 km of railway). The bank had enormous capital because it had seen its fortune during the Civil War, when the Union, to finance the war, had sold government bonds through Jay Cooke for an amount of $500 million, or one-fifth of the entire national debt.

These factors caused an allocation of resources that was too high in railways compared to what they could have earned in the immediate future: in other words, there were not enough “consumers”, meaning people who would have spent money to use those railways, to repay the resources invested in their construction. In free market situations, overproduction phenomena like this can occur, but generally they are limited in time and space, since the market adjusts quickly, even through failure, to find a new and more efficient balance. However, these crises become systemic and large-scale when distorting factors such as state incentives/disincentives and monetary policies intervene. Interestingly, the 2007 housing crisis has very similar causes to those of the railways in 1873.

When Jay Cooke & Company failed in 1873, the bubble burst. The combined effect with the condition of miners and farmers in the West prolonged the crisis until 1877, which saw the first mass strikes (Great Railroad Strike). By now, the late 19th century was shaping up as a modern economy, with overproduction crises, strikes, and interest groups exerting political pressure.

Firefights broke out between strikers, police, and private railway militias. About a hundred people died during the strikes of the summer of 1877.

It is interesting to note the increasingly dominant role of the State, becoming a key player in influencing the market and creating distortions and imbalances, then ironically invoked as a cure by its citizens. At first, state policies created inflation to finance the war, making debt more convenient and thus encouraging farmers to borrow from banks. At the same time, the legal ratio between gold and silver expressed in dollars incentivized miners to operate at costs higher than the revenues they would have earned in a free market from the sale of silver, thereofre resulting in a over-concentration of resources in that sector, producing inflation through the minting of silver dollars. Later, other state laws suddenly eliminated these incentives, causing deflation that hit the profits of farmers and miners. Finally, subsidies to certain sectors of the economy, such as the railways – financed even through public debt – incentivized the development of speculative bubbles. The main protagonists of these bubbles were precisely those credit institutions that had prospered thanks to the State, such as Jay Cooke, with the sale of public bonds. State policies were not only the cause of crises but, precisely because they were the cause, they were also seen as the possible solution. This era of relative freedom and prosperity actually hides the prelude to what would become the degeneration of the 20th century: the all-powerful State that commands the economy and society, the life and death of citizens.

The silverite movements, with the support of miners and farmers, managed to convince Congress to adopt the Bland-Allison Act in 1878, which obligated the state mint to coin $2.5 to $4 million worth of silver by purchasing an equivalent amount of silver, in order to maintain the bimetallic regime and the stability of the silver price. However, the Bland-Allison Act could not do anything against the trend of the price on international markets, and silver dropped from $1.16 in 1878 to $0.94 per ounce in 1889. Under further pressure from the silverite movement, Congress passed the Silver Purchase Act (1890), under which the Treasury would purchase, in addition to what was established by the Bland-Allison Act, another 4.5 million ounces of silver.[7]. At that point, only British India was buying more silver than the United States, as the rupee maintained a silver standard (which greatly disadvantaged the Indian economy in the long run).[8].

These interventions by Congress, which attempted to regulate the price and use of silver as currency by creating “artificial” demand from the State, were once again detrimental to the American economy. The exchange rate between gold and silver was still fixed by law, and those who presented raw silver at the Treasury received dollars redeemable in both metals in exchange. In a world that was already interconnected at that time (banks like Jay Cook were already making massive use of the telegraph in the 1860s), this was an incredible opportunity for traders, as gold in the commodity market was worth more than silver, compared to the exchange rate legally imposed by the state for the creation of dollars. Traders could speculate by buying gold dollars with raw silver, selling the gold contained in these dollars on the metals market, and with the profit, buy raw silver again, then buy gold dollars again from the Treasury, and so on, recursively. In this way, the American Treasury soon ran out of all its gold reserves. Moreover, according to Gresham’s law, “bad dollars” of silver were used for transactions in the economy, while gold was jealously hoarded by individuals as a reserve. Gold soon disappeared from circulation.

In the photo, the construction of the first transcontinental telecommunication line is shown: the telegraph line that crosses the United States from New York to California, completed in 1861.

Basically, the United States was unconsciously shifting to a monometallic monetary system with silver as the underlying asset, where the price of raw silver was lower than the nominal value printed on the dollar. Since the dollar appeared weak, deprived of much of its gold reserves, European traders began to sell shares of American companies in exchange for shares of funds with gold as the underlying asset. Similarly to the previous two decades, the “panic” broke out in the markets in 1893, with a crisis that lasted until 1897. In 1893, President Cleveland repealed the Silver Purchase Act, which was considered the main cause of the crisis.

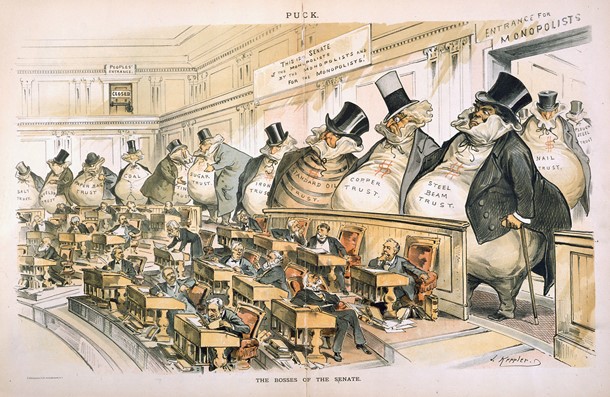

A cartoonist of the time (J. Keppler) portrays the American Senate as if it were controlled by large private monopolies.

In the 1890s, the People party emerged, allied with the labor movement. It was a highly critical party of “capitalism”, particularly opposed to banks and railroads. The latter were certainly not well-regarded by wage laborers, especially after they enlisted private militias to supplement federal forces in suppressing strikes. Banks, on the other hand, besides irresponsibly financing railroads with depositors’ money, were advantaged by deflation at the expense of indebted farmers. However, there arose that dangerous misunderstanding that characterizes any movement or party dedicated to restricting entrepreneurial freedoms and increasing the power and intervention of the State: what actually harmed wage laborers and farmers was not the capitalist element of big businesses (private property, the market price system, profit, and capital accumulation), but the distortions directly attributable to the political and monetary system managed by the State. It is not the lack of state control over railroads and banks that damages the economy, but rather the preponderance of the State in these sectors that sends them out of control.

Even today, the most heavily regulated economic sector is the financial sector, which is instead pointed to by all populists as the paradise of turbo-capitalism. If there were truly a free market in the financial sector, rather than tight state control, with licensing, protectionism, state bailouts, monopolies, and privileges, we would not have public incentives for the now institutionalized fraud of fractional reserve banking, nor the systematic redistribution of wealth from producers to parasites.

With the systemic crisis of 1893, which involved banks and businesses worldwide, the unemployment rate in some American states reached unprecedented levels: 25% in Pennsylvania, 35% in New York, and 43% in Michigan.

At this point, it is however necessary to make a clarification. Free market is not a magical paradise of white rabbits hopping through pink clouds. During that period of strong growth, there would still have been inevitable difficulties, such as temporary spikes in unemployment rates. In fact, job loss is the natural consequence of rapid technological progress: production processes are streamlined, labor becomes less necessary for automated processes, and workers must find employment elsewhere. Unemployment in the short term is therefore an inevitable readjustment of expanding markets. It should be noted that at the end of the nineteenth century, per capita GDP was constantly growing every year: steel and iron production more than doubled in large industrial countries, the price of iron and cotton was halved, and that of wheat decreased by a third. Previously inaccessible luxury goods were now accessible to everyone. Countries with free traded became specialized in production of goods and services where they had comparative advantages. This partly went to the detriment of local producers, as it was more convenient to import from abroad what they locally offered. In the face of greater global prosperity, some segments of the population were therefore affected. State protectionist intervention, to guarantee the status quo for these productive classes, is detrimental to humanity and, in the long run, also affects those whom the State intended to protect.

Given the speed of progress and the rapid changes in the production patterns, no occupation can guarantee the same remuneration forever, and some occupations were completely cut out of the market over time. In such a dynamic and rapidly expanding context, the less is the labor mobility and readiness of people to change habits, the more difficult it will be for workers to find a quick alternative to their current occupation. It is the price to pay for progress.

After the curious political ballet of the dollar between gold and silver, the repeal of the Silver Purchase Act by President Cleveland (1893) marked the end of an era. The price of silver, artificially kept high by the United States government, dropped from $0.94 per ounce in 1889 to $0.60 in 1894. Banks began to discourage the use of silver dollars: it was now clear that gold would be the new standard for the United States. Having only one metal as the underlying for the dollar would avoid the disruptions caused by variations in the price ratio between gold and silver. In 1895, the government closed the Carson City mint and ended the production of silver dollars. In 1900, the transition to the Gold Standard was officially enacted through legislation, establishing that banknotes could be redeemed only in gold at the Treasury. The dollar thus became a title over an exact quantity of gold held in reserve.

In the movie adaptation of The Wizard of Oz (1939), which was shot in color, Dorothy’s shoes are red instead of silver. Even the characters such as the lion, the scarecrow, and the tin man represented caricatures of people from that time.

The book The Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, is an allegory of the monetary history of that period. Oz is short for “ounce”, the most common unit of measurement for gold and silver. The wicked witch of the East, who derived her power from the silver shoes, probably symbolizes the banks of the East profiting from the deflation caused by the lack of new silver coins being minted. The wicked witch of the West, on the other hand, represents the drought that hit the farmers of the West during those years (the witch is defeated by Dorothy, who melts her with a bucket of water). Dorothy, the protagonist, who wears the silver shoes taken from the wicked witch of the East, may symbolize traditional American values that led the silver movement towards the White House (the Wizard’s palace, located in the Emerald City, Washington, green like the banknotes). However, the path to the Wizard of Oz is made of bricks of gold, representing the new gold standard.

The new monetary standard proved to be a much simpler and more stable system than bimetallism. GDP growth up until the First World War (1914) was never affected by problems attributable to monetary policies. The only crisis event in this period for the United States was the panic on the markets of 1907.

The crisis of 1907 is significant because it occurred despite the gold standard system, meaning that the cause was not due to wrong monetary policies. It was precisely this crisis, in the eyes of bankers and politicians at the time, that justified the creation of a central bank. The Federal Reserve (FED) was established six years later in 1913, with the belief that regulation could make the market wealthier and more efficient, which instead fails when left to itself.

It should be specified that the crisis of 1907 was not particularly severe in terms of the country’s production and wealth. The per capita GDP fell by 10% in 1908 and returned to pre-crisis levels the following year. To make a comparison, during the Great Depression of 1929 (i.e., after the establishment of the Federal Reserve!), the GDP constantly fell between 1929 and 1933, with a 32% drop over four years, returning to pre-crisis levels only in 1937.[9] [10]

As we will see shortly, the underlying causes of the 1907 crisis were indeed the inherent weaknesses of the banking system, unable to cope with withdrawal requests due to fractional reserve banking. However, there is always a triggering cause for a bank run, and in this case, the state and the public administration in general played a key role in history. A villainous role, of course.

One of the first causes of the panic can be traced back to the failure of the Knickerbocker Trust, one of the largest banks in New York, due to a very risky bet. The company bought huge quantities of copper at prices higher than market ones, hoping to trigger a price increase. The specific term for this type of operation is “cornering the market”[11]. In today’s common parlance, we would say that it is the attempt of a whale to trigger a wave of FOMO (fear of missing out), inducing a massive quantity of small investors to buy, so that the company can resell at even higher prices. However, it was a failed strategy: the price of copper did not rise enough and the bank was declared insolvent, triggering a bank run that also spread to the company’s branches. Given the sudden demand for withdrawals, these had some difficulty honoring them, thus sowing doubts that the insolvency situation was widespread.

However, the failure of a single company would not have been enough to trigger a general crisis, the causes of which are many, including even the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Above all, state regulation contributed to the collapse of the stock market, thereby also bringing to their knees those credit institutions that had financed companies in exchange for their shares as collateral.

A cartoon of the time portrays Theodore Roosevelt leading two bears (symbol of the bear market) on Wall Street. The president sued 45 companies using the Sherman Antitrust Act

- The Hepburn Act, passed in February 1906, gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to establish a maximum ceiling on railway tariffs, setting “fari, just and reasonable” prices. It came into effect in July and by September, the stock prices of railway companies had collapsed. According to some historians and economists, this law not only impacted the market of the time, but caused much more damage, marking the collapse of the railway business in the United States throughout the twentieth century, which was gradually replaced by the unregulated road transport.

- Another blow to the stock market was the $29 million fine imposed by American antitrust authorities on Standard Oil Company of Rockefeller. It is worth noting that a few years later, using justifications similar to those of a communist State of police[12],the Supreme Court even declared the company an illegal monopoly, dividing it into numerous smaller companies.

After the collapse of the Knickerbocker Trust and the stock market, the situation in October 1907 was precarious. Many financial institutions that had adopted risky investments would not have withstood the market downturn or the demands for withdrawals from account holders. To cope with a crisis that could have caused the weak banking system to collapse, J.P. Morgan persuaded thirteen banks to raise over 30 million dollars to save about 50 brokerage firms[13], and summoned the presidents of various companies to raise 8.25 million dollars to save the “Trust Company of America”. Rockfeller, in turn, deposited 10 million from his wealth to save the National City Bank. A consortium of private banks, the “New York Clearing House,” intervened to settle the debts between banks for 100 million dollars, leaving as many banknotes as possible in the most exposed banks that had difficulty honoring withdrawals from account holders. But it was not over yet, the city of New York declared that the public administration would be insolvent if it did not obtain 20 million dollars. JP Morgan saved the city by negotiating the purchase of 30 million dollars in public debt securities.

Banks and companies were heavily indebted and the bursting of the bubble exposed the gap between the money invested in those companies and the value they actually produced. The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TC&I) was on the verge of bankruptcy, and with it, Moore & Schley, one of the largest financial intermediaries that had financed TC&I in exchange for its shares as collateral. A collapse of these companies would have likely meant a collapse of the entire banking system. JP Morgan convened a meeting and locked up the most important bankers in the city library until they reached an agreement. The solution was the acquisition of TC&I by U.S. Steel. President Theodore Roosevelt suspended the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act to allow the acquisition. The agitation in the markets subsided and the repercussions on the real economy lasted less than a year.

Cartoon depicting J.P. Morgan as a pied piper who enchants and leads a crowd of professionals from different trades.

Bankers and private companies were able to temporarily fill the balance sheets of other private companies, even those of the New York public administration. So the solution to the panic in the markets was actually a rescue operation that flooded immediately insolvent entities with liquidity (through loans) in order to limit systemic contagion. But in this way, the weaknesses and vices of the entire system were hidden, preventing a natural defense mechanism by citizens: withdrawing their money from banks and letting reckless bankers fail. However, the elite of the time believed that this type of “rescue” could be institutionalized, thus creating a lender of last resort, namely the Federal Reserve.

In reality, the establishment of a public entity for this purpose is not at all the way to solve a structural problem, but rather it encourages the market to risky behavior and indebtedness for speculative purposes, since there will always be the central bank to act as a cushion and alleviate the fall, covering losses with public resources (inflation is an indirect tax paid by citizens!). The system can therefore procrastinate for years a situation of a bubble, inflating prices through the flooding of liquidity injected on credit or with fractional reserve, or even more blatantly created out of thin air [14].

The price, as Hayek taught us, is information. Therefore, a distortion of prices has repercussions in the real economy, because economic agents are guided by wrong information, leading to the excessive allocation of resources in some markets, taking them away from others, without the added production of such sectors bringing value to society, since it does not reflect an actual real demand from consumers. Hence, the crisis of “overproduction,” the creation of bubbles, boom-and-bust cycles.

With bailouts, therefore, the structural problem is exacerbated rather than solved, procrastinating the “bubble” situation. The resulting fall will be more devastating. And even if there is no clear fall, because banks are continually saved using public resources, the general redistribution carried out by the system constantly drains resources from those who are productive and gives them to those who speculate. Thus, parasitism, injustice, and poverty are generated. That the FED system is worse than the gold standard will be crystal clear with the Great Depression of 1929, a crisis of unprecedented proportions.

In 1913 the FED was created with the political mandate to maintain stable prices and promote full employment. During the First World War, the convertibility of banknotes into gold was suspended in all major Western countries to finance the war through inflation. Between 1921 and 1928, the money supply in the United States increased by 60% to a total of 28 billion dollars, while the FED’s gold reserves increased by an amount equivalent to only 1.16 billion dollars. In 1929, the biggest crisis of the 20th century occurred, known as the Great Depression. Citizens completely lost faith in the monetary system, presented themselves at bank counters to deliver banknotes and withdraw the underlying gold, which, however, was insufficient. To save the banking and FED system, Roosevelt in 1933 stopped all banking transactions and closed banks for 8 days (bank holidays), while with Executive Order 6102 seized all the gold of Americans, who were legally obliged to deliver it to the Treasury by May 1 in exchange for banknotes at a fixed value of $20.67 per ounce. To take advantage of such coercive power over his citizens, the president exceptionally used the Enemy Act of 1917, which guarantees extraordinary powers in wartime, but was specifically amended in 1932 to be usable in peacetime as well. He thus put an end to the Gold Standard, inaugurating the New Deal. In the same year, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in a Germany destroyed by the Great Depression and inflation, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the Reich. Thus, in the 20th century, wherever the all-powerful State rises as the master of our freedoms, amidst the applause of socialists, nationalists, and their foul-smelling hybrids.

- Bitcoin the solution

If a Bitcoin standard had been in place instead of a metallic or fiat standard, many of the problems of the time would not have occurred. Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that everyone in the 1800s had access to a Bitcoin wallet. The State would not have been able to create inflation or deflation, as the supply of Bitcoin is fixed. This would have also prevented unexpected redistributions of wealth between creditors and debtors, such as what happened between western farmers and eastern banks during the 1870s. In that case, the farmers would have borrowed from the banks, fixing an interest rate congruent with the expected appreciation or depreciation of Bitcoin [15], so they would not have been subject to a redistribution of wealth to their detriment and in favor of the banks caused by the government.

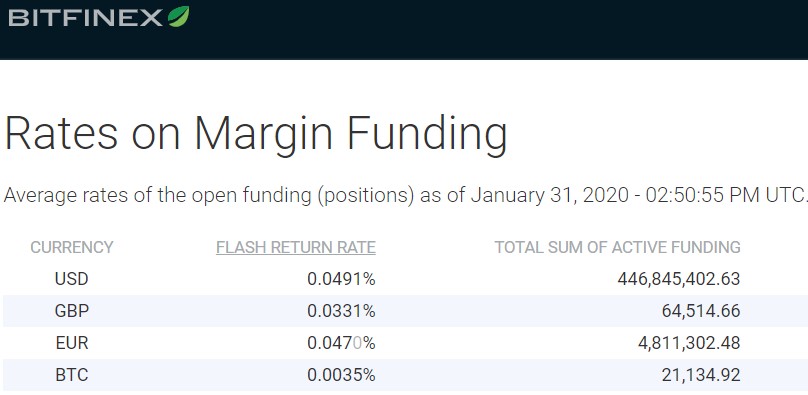

Average daily interest rate paid on Bitfinex for loans in dollars, pounds, euros or bitcoin for margin trading (as of January 31, 2020)

Note that not even the gold standard guarantees the same freedom as Bitcoin. In fact, gold has an insurmountable problem: its physicality. The cost of transferring the underlying asset, as well as the difficulty in securing it without entrusting it to third parties, makes intermediaries necessary, and therefore banks. The modern economy is too fast-paced to wait for the physical movement of gold, so it becomes the underlying asset for various types of bearer securities (banknotes, electronic currency) that end up being more manipulable and controllable by particularly powerful or influential entities. It is inevitable, therefore, that, as has always historically been the case, the gold standard degenerates into a centrally controlled system, which does not happen in the case of Bitcoin. By eliminating the need for an intermediary, the risk of misappropriation by commercial banks is also avoided, thus completely preventing monetary expansions made through fractional reserve banking. Without monetary expansions, there would be no overly cheap money that incentivizes risky investments, making speculative bubbles and systemic crises less likely.

[1] 18,000 business bankrupt, of which 89 railway companies

[2] 8% according to other sources, anyway double the previous situation. See Panic of 1873 on wikipedia.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction_era#National_financial_issues see the works of Unger, Myer, Robert and Studenski.

[4] With the Public Credit Act of 1869, the Treasury cyclically sold gold, about every two months, strongly impacting the price of the yellow metal. This volatility attracted some speculators, especially Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, who thought they could manipulate the market price, even using illegal means, including bribing politicians who managed the gold sales and intimidating other traders. In September, Gould and Fish pushed the price of gold in a full-blown bubble, when President Grant ordered a massive sale of gold for $4 million (in today’s purchasing power, about $150 million). It was Friday, September 24, from which it passed into history as Black Friday. The price of gold fell in just a few minutes from $160 to $136 per ounce (a drop of about 15%). The recurrence of Black Friday is now celebrated as a day of compulsive shopping with discounts on Amazon and Steam, but at the time, it was a hard blow for many.

[5] In 1869, Grant sent a letter to his secretary stating that deflation would harm Western farmers. In reality, this information had been instilled in Grant directly by Gould and Fisk, who hoped that the president would halt gold sales in order to further drive up the price (see note on Black Friday).

[6] For example Jay Knox, at that time “Comptroller of the Currency”

[7] more or less the equivalent of 4.5 million dollars, since price per once in that period was closer to 1 dollar

[8] Since the Indian currency, being backed by silver, was worth less than Western currencies, Indian products were sold at a discount to Westerners who could afford silver with “less effort”. According to Saifedean Ammous, the detachment experienced by China and India from the West during this era is due – in part – to this monetary factor, namely the weakness of the local currency, “easy money” for Westerners who had an abundance of silver at relatively low prices. A strong currency compared to its counterpart guarantees much greater bargaining power. An analogy can be made with semi-primitive tribes colonized by Europeans, who granted precious goods, which require hours of hard work to produce, in exchange for items that were difficult for them to produce, such as glass beads that represented the local currency (which instead were easily produced by Western factories).

[9] Maddison projet db. Download excel with GDP per capita. https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2018

[10] https://bfi.uchicago.edu/insight/chart/u-s-real-gdp-per-capita-1900-2017-current-economy-vs-historical-trendline/

[11] the same operation of Gould and Fisk the Black Friday 1869

[12] According to the court “ “The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Co. charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher” (Jones Eliot, The Trust Problem in the United States, 1922)”. From this passage it is evident that the actions of Standard and Oil described by the Supreme Court are completely in line with the behavior that one might expect from a free enterprise in a free market, without having anything wrongful.

[13] 23,6 million dollars on tuesday 24th October and other 9.7 million dollars on friday

[14] Open market operations by the central bank (quantitative easing), where government securities and potentially also private corporate bonds are purchased to push stock prices upwards.

[15] The scenario envisioned is obviously in the presence of already achieved mass adoption, so once the period of frenzied Bitcoin price surges is over. Once bitcoins are well distributed among the population, their price rises compared to goods and services traded in the economy if these increase at a greater rate than the value of new bitcoins produced through mining (because there will be relatively fewer bitcoins compared to traded goods). Conversely, if the production and supply of new bitcoins exceeded the demand for new traded goods, bitcoin would depreciate. In both cases, these are limited and more predictable deviations compared to the situation of the dollar: in the case of Bitcoin, the money supply is fixed, and the unknowns in the equation are only production and global trade; in the case of the dollar, instead, even the supply of dollars is an unknown, depending on the whims of politicians and bureaucrats.