The Heroes of Modernity:Jesus of Nazareth, Anakin Skywalker, and Satoshi Nakamoto57 minuti

All three fight against evil and sacrifice themselves for us – each representing different yet fundamental aspects of contemporary humanity.

DISCLAIMER: This article is frivolous in nature and claims no scientific validity. The theses expressed are purely suggestive. Furthermore, I’ll reveal mind-blowing spoilers like how the Gospel ends, all about the expanded universe of Star Wars, and the identity of Satoshi Nakamoto.

TABLE OF CONTENTS: this article’s table of contents section will vary depending on which of the following personalities you align with. Read each carefully and then proceed.

Personality: Joseph – son of Jacob and interpreter of dreams.

Read the article as a narrative from beginning to end – gradually uncovering how the puzzle pieces together from Christ to Darth Vader to Bitcoin. Unlike the calculating maniac below, you don’t need an index or preview to give you an overall logical view. Once you’ve finished reading, leave a comment stating your personality.

Personality: Palpatine – Sith Lord, Master of the Galaxy

You’ll find the table of contents at the bottom of the article. I won’t ask you to comment on which personality you are, as you probably wouldn’t do it anyway.

Personality: Michael Saylor – BTC Hodler (of many BTC, indeed)

Fuck the table of contents. Scroll and read where your eye falls. After all, you’ve gone all-in, so you can rely only on luck and intuition. You’ll find precious gems here and there.

Jesus, the defeated hero

Jesus of Nazareth is undoubtedly one of history’s most absurdly powerful heroes.

He’s the hero who doesn’t win but dies, tortured, and killed. He rises again, but there’s no real comeback where he returns with wings of fire to beat up his enemies and shower faithful followers with milk, honey, and women.

On the contrary, just before he breathes his last, he exclaims, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?). In short, not only is the hero abandoned, but he declares himself as such. He is defeated. And even at that point, when he is dying on the cross, there’s no deus ex machina to roast the centurions below.

All you hear is mighty thunder, and that’s it. Jesus dies, period. He’ll peek out three days later for a goodbye to friends before returning to heaven. Just a brief private chat. He certainly didn’t manifest among lightning and thunder to conquer Rome. Long story short, he bites the dust, and that’s it.

It’s surprising how the story of Jesus took root over two thousand years ago when heroes included Gilgamesh or Achilles, and gods were entities like Mars or Sekhmet. Imagine today how strange it would be for an Avengers movie to end with the hero croaking like that after the Via Crucis and yelling to his father, “Why have you forsaken me?”

And yet, Christianity conquered the world and had a substantial cultural and political impact.

Jesus’ message was undoubtedly innovative and remains original today: to be good for the sole purpose (at least earthly) of being good. Love is indeed a distinctive trait of Christianity compared to previous doctrines, even compared to Roman virtues of Caritas and pietas, which were much more pragmatic, living within a more collective than a personal sphere, serving as social glue.

Instead, Christian love is much more introspective, a source of individual joy, detached from traditional direct indicators of individual or social well-being like wealth and power. These are related to the satisfaction of primary needs for humans at a biological and anthropological level: food, health, security, and social status (the latter relevant for courtship and mating purposes).

The success of Jesus between instincts and reason

It is interesting to understand how Jesus’s teachings, seemingly so distant from human aspirations from an evolutionary perspective, such as the accumulation of wealth (primarily survival, then power, and finally progress), have nonetheless captured the hearts of millions of people across all social classes.

It could be that animal species like ours have natural instincts that align well with Jesus’ message. Our species and many mammals, birds, and even some reptiles have maternal, paternal, or fraternal instincts to care for offspring and family.

Perhaps Christian love and solidarity for others can be seen as an extension of this fraternal instinct to a community. It could be that forms of kindness or altruism have rooted in us for evolutionary reasons, improving the species’ survival prospects through a push towards mutual aid.

It’s no coincidence that, unlike species that have imposed their supremacy through force, the dominant species on Earth, humans, excel in cooperation, which enables trade and division of labor and thus progress.

In our interactions, altruistic love is an emotional (and intuitive) element that, when exercised, gives us sensations comparable to the sense of well-being we experience when satisfying our primary needs or needs directly related to survival.

The joy of mutual giving can resemble the satisfaction we get from eating, resting, mating, winning in battle, or in play (which is a bit like battle, as the evolutionary utility of play is ultimately to prepare us for combat). Emotional elements and positive neurobiological responses drive us to choose reciprocity through love or the negative sense of guilt.But is it only instinct, or is this predisposition somehow “learned”? Supporting the instinct theory is that altruistic behaviors are observed in animals, especially primates, to the extent that theories suggest we are genetically programmed to be “good” (1). Therefore, a doctrine of love and altruism like Christianity would easily win people’s hearts, given a natural and intuitive predisposition in some animals and humans towards altruistic love (2).

High levels of complexity in animal social relationships may lead us to think that goodness and altruism have also developed due to a conscious decision to adopt advantageous behaviors. This decision could be an individual’s or, for some species, a decision-making mechanism passed down over time, thus becoming part of the group’s culture.

Returning to the human element, Jesus’ message may have conquered societies of the time not only because it leveraged instincts and emotions but (also) because it would have met a natural process of human reason that recognizes a certain validity in the message of reciprocity, perhaps deeming it beneficial to achieve greater individual and group well-being.

Morality as a biological heuristic shortcut

There are theories suggesting that moral principles result from rational and strategic calculation. I’ll briefly mention the prisoners dilemma separately

to avoid weighing down this article. In short, according to the theory, there are cases where, despite the immediate advantage of pursuing individual interests at the expense of others, collaboration in the long term could be much more profitable when there are repeated social interactions with the same people.

In the absence of perfect information, unable to know when the other person will no longer be helpful to our goals, continuing to help each other could be advantageous indefinitely. So, according to such theories, “altruism” would be the outcome of mere utilitarian calculation.

In reality, I believe that emotional and instinctive responses can also be relevant in choosing the solution that is deemed rational. And we’re talking about “emotional responses,” which are innate and learned.

Making optimally rational decisions through instinct can work like an athlete relies on muscle memory, developing new instinctive responses to specific events. Cooperation is beneficial in the repeated prisoner’s dilemma model. Still, the individual can’t know how long it will be helpful to maintain reciprocity because our information is limited, and the future is uncertain. We cannot anticipate the thoughts and moves of others.

Without morality, the doubt of “When will I be betrayed? Should I betray first?” will always linger in our thoughts. Without a moral sentiment, triggering collaborative behaviors, which initially require trust in the other’s promise (their word given), would be much rarer, and maintaining such collaboration beyond the time horizons calculated by the individual would be even more unlikely.

Committing to calculating the outcomes of our actions at every stage of our social relationships is costly in terms of time and energy. Constantly posing the rational choice between cooperation and non-cooperation is demanding.

The economist Coase would include such a choice in what he calls “transaction costs”, akin to an entrepreneur who continuously incurs costs in renegotiating contracts and changing suppliers. For this reason, emotions and instincts can be helpful.

Morality is a biologically-based heuristic shortcut that resolves the rationally unsolvable dilemma of choosing between cooperation and non-cooperation, extending the temporal horizon of cooperation even when there isn’t a rationally well-defined horizon and cutting costs, stress, and anxiety of conflicts. It allows us to find the right path when it would be too costly or impossible to do so rationally.

This mechanism, ultimately, provides an impulse to the progress of humanity and leads to the natural selection of more cooperative human beings and more peaceful civilizations. Just like Bitcoin! (don’t laugh, jerks! Finish reading first).

One might wonder whether there is an ultimate evolutionary purpose of morality, such as the promotion of the individual and, therefore, indirectly, the species, or perhaps primarily the promotion of the species, even through the altruistic sacrifice of the individual. In reality, it’s more likely to be neither. There might not be an ultimate evolutionary purpose at all, meaning there is no purpose (or “destiny”) in the force that drives us towards love and cooperation.

Instead, it’s chance, like genetic mutations in Darwinian theory, that has combined certain factors in us that have selected humans, making them cooperative and, therefore, successful animals. In short, we dominate the Earth because, by chance, we find ourselves loving.

Conquering the world without violence

There are two ways to conquer goods, wealth, lands, power, capital, women, and technologies.

The first is violence, typical of bandits, criminals, raiders, rapists, mafias, or other unwanted protectors, such as states and political and social organizations, generally directed towards wealth producers, applying taxation or, more rarely, confiscation.

Or even externally, through war. In any case, the application of violence, or coercive power that uses violence as a threat or deterrent, is always a zero-sum game: wealth is transferred from some individuals to others, and in the process, some is always lost due to inefficiencies, damages, or distortions.

One of the most efficient methods of wealth redistribution through violence is robbery, typical of a street criminal. If nobody gets hurt, the net loss of “social utility” is relatively low: the victim who lost their wallet will have to request the re-issuance of all bank cards, identity documents, etc., incurring some costs in terms of time and money.

Furthermore, the nice leather wallet will either be thrown away or resold for less than it was subjectively worth to the original owner. However, at the very least, the cash obtained from the theft equals what the victim lost.

On the contrary, state taxation is one of the most inefficient and distinctly immoral methods of wealth redistribution through violence. I’m sorry for those academic economists who still believe they can maximize social utility through taxes, debt, and government spending. There are several particularly mainstream examples in Blanchard’s Macroeconomics and McGraw Hill’s Public Finance. I would refer them to educational readings such as this one.

Individuals’ consensual, voluntary, and spontaneous agreement is an alternative, evolved, and civilized form to obtain wealth and progress. It always takes place through private forms of negotiation, such as contracts and commerce.

Commerce is an act of self-love (because we buy what we like), but unlike violence, others also benefit from it (because they receive what they want in exchange). It is based on the most basic moral principles that underpin our humanity: keeping promises and honoring one’s word. It is always a positive-sum game, as consensual exchange is beneficial by definition to both parties and allows for the specialization of individuals in different jobs, with sectors that, over time, accumulate more capital in the form of productive means and knowledge and technology, thus progressing further.

Not only does commerce strengthen social relationships among individuals and encourage peaceful and fruitful coexistence, but it also promotes diversification, allowing each person to find their vocation in what they are most passionate about. Just like Bitcoin! (and again, don’t laugh, jerks! Finish reading first).

Jesus against Caesar

Authorities are inevitably attracted to the wealth and power that arise from exchanges.

Established power has always sought to control trade in every way, from small-scale monitoring by local authorities and random checks by the tax authorities to exchanges in international routes patrolled by American aircraft carriers. This control is exercised not only by dominating the main communication routes but also – and above all! – the means used for exchange, especially money.

Control over exchanges guarantees privileges and extraordinary power, exploited in all ages, reaching dizzying peaks in the regimes, even democratic, of the 20th and 21st centuries. Jesus is among the historical figures who metaphorically opposed this power, not recognizing monetary authority.

The famous phrase “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God, the things that are God’s, and unto men Bitcoin” (at least, that’s how I remember it) hides a deeper meaning than simply disavowing administrative and monetary authority. And I say this even excluding the final part about Bitcoin, of which I doubt its historical accuracy.

When the first gospels were written down, according to some estimates, around 70 A.D., inflation was a burning issue in imperial Rome. Until Augustus, Rome had maintained a strict monetary regime. Still, the minting of new coins in the lands conquered by the Empire was not easily controllable, as generals and local governors, through mobile mints, managed it. It was, therefore, possible for new coins to be counterfeited by mixing lesser metals with silver.

The Senate had strict rules, and Augustus had reformed coinage to ensure greater uniformity; however, his reform brought the minting of aureus (gold coin) and denarius (silver coin) under direct imperial control.

It took only a few decades for this power to be abused, and already under Nero, a denarius was coined with 10% less silver, essentially allowing Nero to purchase goods and services with 10% more purchasing power, created “out of thin air,” for every coin forged. Essentially, it was an invisible 10% tax on all denarius holders in the empire at a time when the only existing tax was 1% on assets, up to a maximum of 3% in emergency cases.

One of the leading causes, perhaps the first ever, of the decline of the Roman Empire is inflation. Within two centuries, devaluation was dramatically exponential, destroying stability, trade, social fabric, and peaceful cooperation among peoples under and near imperial rule.

| Date | Emperor | Inflation* | Average annual inflation |

| 200 AD | Septimius Severus | 200 | 0,7% |

| 215 AD | Caracalla | 267 | 3,65% |

| 250 AD | Trajan | 300 | 3,65% |

| 274 AD | Aurelian | 700 | 3,65% |

| 293-301 AD | Diocletian | 1400 | 22,9% |

*100 = denarius under Augustus

Under Tiberius, when Jesus lived, the imperial denarius was still relatively stable; however, coins minted with mobile and dissimilar mints could arouse suspicion. In any case, the denarius was already wildly inflated when the authors of the gospels wrote, which supports the interesting interpretation of some gospel passages by Claudio Ferrari in his book “Cos’è il denaro, cos’è il Bitcoin” (What is Money, What is Bitcoin, only available in Italian) (2023).

Judea was a Roman province for less than 30 years at the time of Jesus. Various coins circulated in Judea, including the Tyrian shekels, the drachma, and various denominations of Roman coins.

The Temple in Jerusalem was an important institution even economically, as it housed a huge treasure and acted as a bank by making loans with interest. The Temple did not accept offerings in Roman denarii but in Tyrian shekels. The Pharisees tried to trick Jesus by asking him whether paying taxes to the Romans was right.

By showing a Roman denarius and saying the words, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s,” Jesus urged to get rid of Roman money to pay taxes to the Romans (which were obligatory, under penalty of slavery), but only limit its use to that, certainly not to make offerings to the temple, which was the most prestigious bank in all of Judea!

Ferrari’s interesting explanation is that the rejection of Roman coins was not due to religious reasons. In fact, as the denarius depicted Caesar, the same could be said of the shekel that represented Hercules Melquart, equally distant from the Jewish religion.

Instead, it was the quality of the coin that made the difference: the denarius could be corrupted, with a nominal value engraved on the coin different from its actual content, while the shekels were uniform pieces of pure silver of known weight that all came from a single mint.

Furthermore, one can also interpret Jesus’ words as an exhortation to “return” to the Romans’ own money, paying taxes to the least possible extent (just enough to appease the imperial extortioner) without enriching them by tapping into local resources.

In short, the Pharisees and Herodians were not “amazed” by Jesus’ response because he shot the spiritual bullshit of the division between the earthly world and the afterlife; on the contrary! They were amazed by the political cunning with which he accused the system, using at the same time an unassailable dialectic.

In several other episodes, Jesus mentions coins precisely, underlining the attention given to the different denominations of coins and their relative value.

Referring to just one of the many examples reported by Ferrari, in the parable in Matthew 18:24, the Good King forgives a subject a debt of ten thousand talents (a unit of measurement of pure silver, equal to about 25 kilograms), while the wicked servant does not even forgive a hundred denarii to his fellow servant (Matthew 18:28). The fact of mentioning not only different quantities but also different units of value, talents, and denarii, is not random! Jesus, or whoever the author of the gospel was, wants to emphasize that the King forgives a massive debt in “good” money (the talent), while the wicked servant does not even forgive a small debt in bad money (the denarius).

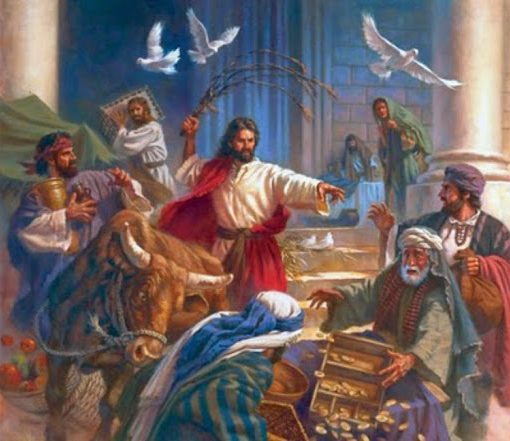

Jesus at the temple, in the well-known scene from the gospels where he overturns the money changers’ tables: “For heaven’s sake, I told you to use lightning!”

In a subdued, defeated land, far removed from the splendors of the Elohim of the ancient testament—likely the great commanders of the Israelites (later deified and reinterpreted singularly as the monotheistic figure of Yahweh)—we encounter a cunning Jesus.

He is aware of the social and economic dynamics, anarchic concerning the new authorities of the Roman conquerors and their monetary tools. He understands that direct confrontation is not an option. In defeat and subjugation, he unveils a profound spiritual and innovative message, one of pacifism and love, sharply diverging from the violent Jewish traditions of a once victorious people.

Jesus is the first of the three figures I have chosen to adopt in this article as representative of an ideal. For this initial chapter, Jesus embodies the perfect ideal of unconditional love and morality, without blemish, fear, or sin.

Love is the ideal that leads us to collaboration, reciprocity, and exchange, urging us to devote ourselves to a more beautiful, good, and joyful world. Love is one of those distinctive traits that has made humanity strong, the dominant species.

We’ll return to Jesus in a bit; we now have darker paths to traverse.

Anakin Skywalker, the monster hero

“I and the Father are one…”

&

“…I am your father”.

Two very well-known phrases, both uttered a long time ago, but only one in a galaxy far, far away. The first was by Jesus, and the second was by Anakin.

Two very different epics, yet the protagonists have many similar aspects. Both are messianic figures, the chosen one, born of the Incarnation (Holy Spirit or midichlorians, it matters little), and who will bring peace to the universe with his extreme sacrifice. Jesus dying on the cross, Anakin sacrificing himself, and finally (forgetting the obscene Disney ending) defeating the Emperor and Sith Lord, restoring balance to the Force.

Jesus was God and man at the same time. Anakin, too, is a man and deity, the Chosen One who must take the place of Guardian of the Force, replacing the Father of the Gods of Mortis (Clone Wars, Season III ep. 15 and later).

Jesus represents the flawless hero who fights evil, a perfect form, and does not succumb to temptation and fear. The attempt to present him as a man is an epic fail for the authors – perhaps the evangelists did not attend the top-quality schools of George Lucas.

Jesus, let’s face it, is almost inhuman. On the other hand, Anakin is the hero who – before redemption – becomes evil because he is too human. He is overwhelmed by fear and suffering, by extremely unfortunate circumstances, and sometimes by forced choices.

Jesus, despite enduring severe beatings and hardship, has a story that, at least in the Christian context, is one of triumph. Anakin is instead the icon of failure.

While Jesus came to redeem us, we watch Star Wars awaiting Anakin’s redemption. We never truly connect with Jesus when we read about him or see him in a movie. The weight of his decisions never truly impacts us because he is portrayed as perfect and infallible.

In Mel Gibson’s “The Passion”, we empathize with the protagonist solely through the physical pain endured. In contrast, with Anakin, we relate, feel the pathos of his poor choices and moral downfall, regret his actions, and yearn for redemption.

While we saw the first films of the ’70s through Luke’s eyes, when we watch them again today, in the light of the expanded saga, the perspective is always that of Anakin, the true protagonist of the saga. While Vader’s black mask conveys profound thoughts as the Emperor strikes Luke with Force lightning, it reveals more emotions than we see in a tortured, dying Luke.

For those unfamiliar with the expanded universe of Star Wars (so the relatively recent TV series in addition to the historic films), I summarize how Anakin, from hero, becomes the perfect nemesis before redeeming himself.

Having a son at the right age and passionate about the genre, I have freshly reviewed the entire saga. For those not particularly interested in extreme nerd onanism practices like the mega-revision of the events of half of the Star Wars saga, you can skip the next chapter or just take a quick look at what I highlighted in bold.”

From Anakin to Darth Vader: The Story

Anakin is born a slave, and when Liam Neeson, as Qui-Gon Jinn, has the opportunity to free him and allow him to follow the path of the Jedi. However, in doing so, Anakin is forced to abandon his mother, who remains a slave (Star Wars Episode I). He will always want to return to redeem her, but he will not have the opportunity until it’s too late.

Anakin’s journey to becoming a Jedi begins, and it’s particularly tumultuous. Jedi are typically peacekeepers, but it’s a time of war, and Anakin is employed by the Republic for three years of battles (Star Wars: Clone Wars, animated series) in which he essentially does nothing but slaughter enemies: robots, aliens, humans, essentially persons.

His main task as a Jedi essentially involves the exercise of force and violence. To win battles and save his loved ones, he also develops pragmatism – applyings non-traditional approaches for the Jedi Order, including the force choke to extract information from opponents. It’s the same iconic technique he will use as Darth Vader, even fatally. For young Anakin, it’s a form of “for the greater good” torture that allows him to save many lives and people close to him. The Jedi’s dogmatism is already constraining Anakin, who looks more at the end than the means, at raisons politique.

Is it permissible to use torture on evildoers to save numerous innocent lives? The answer lies in the eternal conflict between deontological and consequentialist morality (see, for example, Charles Larmore’s Patterns of Moral Complexity), and there’s no simple answer to the question of what is right and wrong.

Now a young adult, Anakin has visions of his mother in peril and travels to Tatooine to save her, but he is too late. She dies in his arms after being tortured by the Tusken Raiders.

He seeks revenge by slaughtering the entire village (Star Wars Episode II). He views his mother’s death as his failure, finds it unacceptable, and becomes convinced that he must do whatever it takes to surpass his limits and save his loved ones. This conviction, combined with his pragmatism and disregard for the precepts taught by tradition, will lead him down a dangerous path.

Since he was a boy, Anakin has been in love with Padmé. He disagrees with the dogmatic view of the Jedi, and, contrary to the Order’s prescriptions, which forbid attachment to others, he decides to marry her.

Consequently, he constantly struggles with having a secret marriage that leads to turbulent couple situations (several examples in Clone Wars, the animated series). Furthermore, he doesn’t share Padmé’s political vision, preferring a more authoritarian policy with a man in command. This fetish for somewhat overly authoritative leadership is unfortunately very common in all epochs and galaxies.

Anakin is a general in the Republic army, and by the end of the Clone Wars (animated series and Star Wars Episode III), he is arguably the strongest Jedi alongside Yoda and Mace Windu, to the point where he easily defeats Count Dooku.

During the wars, it was commonly whispered among worried youth as a common phrase of comfort: “Anakin and Obi-Wan will arrive at moments” (source: Revenge of the Sith, novelization). In short, Anakin was known as a hero, a famous figure throughout the galaxy. Yet, he held the title of “Knight” and was not allowed to sit on the Council as a “Master,” which he saw as an outrage.

His inner conflicts and turbulent character do not grant him the stability and maturity necessary. Anakin believes that the Order and his master, Obi-Wan, knowingly limit his potential. Added to this is that his Padawan learner, Ahsoka, is unjustly accused of treason instead of Barriss and thus expelled from the Order (Clone Wars season 7)—a terrible affront to the young Jedi, plagued by doubts.

As if that weren’t enough, the Council asks Anakin to spy on the Chancellor of the Republic (Palpatine), a character who, up to that point, had always been wise, calm, and intelligent, a fascinating mentor for Anakin whom he greatly respected.

Spying on the beloved Chancellor of the Republic by playing a “double game” did not seem like a worthy task to Anakin, who had sworn to defend the Republic and, therefore, the Chancellor who represented it.

At this point, Chancellor Palpatine reveals to Anakin that Obi-Wan and Senator Padmé are meeting in secret and that some politicians and the Jedi are planning to kill the Chancellor. This information reaches Anakin when he is physically and psychologically exhausted and full of doubts. He is unaware of the chip implanted in the clones to execute Order 66 and exterminate the Jedi. In his eyes, the fact that the Order was spying on the Chancellor could only further confirm Palpatine’s theory.

Anakin truly believes that the Jedi Order could betray the Republic.

He is not aware of all of Palpatine’s schemes to gain more power, such as, among many, the subjugation of the Intergalactic Banking Clan and the transfer of the banking system directly under the Chancellor’s office, thus gaining a monopoly on credit (Clone Wars, season 5).

We have seen in Imperial Rome how this privilege could grant the Emperor almost “divine” power, at least in economic and social terms. Among the amendments to the constitution passed under Palpatine, there was also a revolution of the bureaucratic apparatus, with the introduction of governors for each sector, justified for logistical purposes to provide the best support to the troops stationed across the galaxy. Thus, the Senate has increasingly less control than the Chancellor’s office—typical reforms and powers acquired under the pretext of emergency never to be returned.

Palpatine’s ascent as a skillful and patient strategist is very gradual. He increasingly consolidates power law after law, exploiting fear, anger, conflicts, and propaganda. There are many parallels in our galaxy, from Hitler’s rise to Executive Order 6102, a sort of “Soviet” act with which Roosevelt seized all gold from US citizens.

It was a harsh blow to freedom in a nation that is considered, at least by the masses, among the freest of that historical period. To carry out such a state crime of a totalitarian nature, Roosevelt exploited a law from 1917 (passed during wartime) that granted special powers to the government in case of emergency. To snatch away freedom amid thunderous applause, including from all Keynesian academics, it sufficed to apply the concept of emergency to an economic depression, which, incidentally, was caused by the very institutions themselves.

The Great Depression of 1929 resulted from a period of exceptional monetary expansion, during which the Federal Reserve increased the money supply by 60% from 1921 to 1929. Palpatine, Hitler, Nero, or Roosevelt: every galaxy is the same when too much control is granted to authority.

Sheev Palpatine is a cunning manipulator both in politics and in personal relationships. He can read Anakin like an open book, his conflicts, anxieties, fears, doubts, and friction with the Jedi. During that time, Anakin has continuous premonitions of his wife Padmé suffering and dying.

In the weeks leading up to becoming Vader, he doesn’t sleep due to constant nightmares and doesn’t eat either (source: Revenge of the Sith, novelization). He’s far from lucid. He can’t bear to lose her, too; it would be yet another failure. He must become powerful enough to save her. So, Palpatine finds the right moment to reveal to Anakin that he is a Sith Lord and that in the past, the Sith almost gained such power as to defeat death: together, they can obtain that power and save Padmé.

Anakin knows little about the Sith and the dark side, and he doesn’t have much basis to evaluate that there necessarily is evil in (or in all of) Sith traditions. After all, there are also Jedi techniques that harness the dark side, such as Form 7, derived from Juyo and which Mace Windu (Samuel L. Jackson) reinvented as Vaapad. Windu, the number two in the Jedi Council, effectively wields a purple lightsaber, a mix of the Jedi blue and the Sith red.

Despite his doubts about where evil and good lie, Anakin immediately goes to Windu to reveal Palpatine’s true identity. Windu and a team of Jedi masters then confront the Chancellor in his office to capture him.

After one of the choreographically worst battles in all of Star Wars, Windu, thanks to his Vaapad – the perfect technique against the Sith – manages to defeat Palpatine (who perhaps didn’t exert his full effort, seeking Anakin’s help, though George Lucas himself asserts that he Palpatine was genuinely defeated). Anakin bursts into the room and finds a defeated Palpatine on the ground, with Windu ready to land the executioner’s blow.

So here’s the last straw that breaks the camel’s back: Anakin expects the Jedi to capture Palpatine and arrange a fair trial. Still, Windu refuses, stating that the opponent is too dangerous to be left alive and must be eliminated on the spot.

Anakin is unable to see Windu’s point of view here. After all, he has no evidence of crimes committed by the Chancellor, and there’s not even such an obvious connection between the Sith Lord and the war between the separatists and the Republic.

Although Anakin probably understands that there may have been a double game, it’s unlikely that he comprehends that three years of war were entirely orchestrated by Palpatine. After all, significant social conflicts did exist independently of the Sith.

In short, the theory of Jedi betrayal is more valid than ever. After all, the world of Star Wars isn’t black and white, good and evil; mistakes and betrayals exist in all factions (see, for example, the episode of Ahsoka being expelled from the Order or the story of Dooku (3)). Anakin tries to convince Windu to spare the Chancellor, but he fails. Windu is about to deliver the decisive blow, and at that moment, Anakin stops him in the only way possible: by cutting off his hand. He doesn’t anticipate the consequences of that action: after all, the enemy (Palpatine) is defeated on the ground and can still be captured. However, along with his hand, Mace has lost his weapon to defend himself from the force lightning, and Palpatine kills him with a blast that hurls him out of the window.

Here, Anakin realizes he’s now caught in an irreversible situation: how can he explain to the Order that he helped a Sith Lord kill a Council Master?

The Jedi will hunt him down as they did with his apprentice Ahsoka. Will they try to execute him directly, as they attempted with the Chancellor? Moreover, Palpatine must stay alive because he’s Anakin’s only chance of discovering the dark side powers that can save Padmé. There aren’t many options; Anakin will be forced to fight the Jedi regardless.

And if not the Jedi, there’s an army of clones under the Chancellor’s command. In the immediate term, he can’t confront Palpatine because whatever the outcome of the fight, it could destroy the only chance of saving Padmé.

He decides to pledge allegiance to the Chancellor of the Republic and elect him as his new master. As he will confess to Padmé shortly after, the explicit goal is to learn his secrets to gain more extraordinary powers and then defeat and possibly replace him. Anakin thus submits “temporarily” to Palpatine, who renames him as his disciple: Darth Vader.

Following this, we witness perhaps the most intense scene of the entire saga. Vader and the clones attack the Jedi Temple, and Vader enters the room where the children, young padawans (the younglings), have taken refuge:

Master Skywalker, there are too many of them. What are we going to do?

A child asks him, hopeful that he will see the Jedi knight and hero of the galaxy who could have saved them. Anakin ignites his lightsaber and slaughters them all.

Until now, Anakin’s breaking bad has been gradual and justified. However, as iconic and central (probably the strongest and most brutal in the saga) in Anakin’s character development, this scene feels a bit forced. It would have been more believable for the character to be paralyzed, watching the younglings while the clones burst in behind him and massacre them with blasters.

Indeed, in his Jedi past, Anakin has already killed defenseless people, including young Tusken raiders. Still, they were aliens and strangers, not children who knew him personally and looked to him for help. To justify such a scene, we perhaps need to consider some mental process like “they will be killed anyway, better to do it now in the least painful way possible” rather than an action of pure hatred and wickedness or personal interest in increasing his power through the dark side. In comparison, the choking of Padmé is nothing: a gesture of temporary frustration and jealousy, certainly not deadly. Padmé will die from despair, not from physical harm.

After laying waste to the Jedi Temple, a weary, morally conflicted, frustrated, and wrathful Anakin confronts Obi-Wan and is defeated. Anakin had swiftly dispatched Dooku in less than a minute and was stronger than Kenobi. However, the latter manages to prevail and cut Anakin in two. Partly due to his experience and perfect knowledge of his apprentice, partly because the defensive art of Form 3, Soresu, is an excellent counter to Anakin’s Form 5, but above all because Anakin is in a precarious physical and psychological condition, including weeks of sleeplessness and barely eating.

Cut in two and reassembled in his suit by Palpatine, Darth Vader has a new life and face. He will never be able to recover Anakin’s sword fighting skills, so it will be tough to defeat his new dark master as he intended. Moreover, his suit is purposely designed to be weak against Palpatine’s force lightning.

However, Darth Vader’s determination will lead him to enhance his Force power through the dark side (he will even be able to bring down an AT-AT or stop, pull down, and gut a large ship departing for orbit, as shown in the – unfortunately for the most part ridiculous – Disney’s Obi-Wan Kenobi miniseries).

His growth in the dark side will nevertheless make him increasingly powerful, and twenty years later, he will manage to kill Palpatine by throwing him into the reactor of the second Death Star and sacrificing himself in the process, as the respiratory apparatus of his suit succumbs to the force lightning.

Darth Vader, unlike Palpatine, will never seek power for its own sake. Before the battle on Mustafar, he will tell Obi-Wan that he has brought “peace, freedom, justice, and security. We can end this destructive conflict, and bring order to the galaxy!”. Indeed, he killed the Sith Dooku, destroyed the separatist council, and annihilated the temple of the “traitor” Jedi.

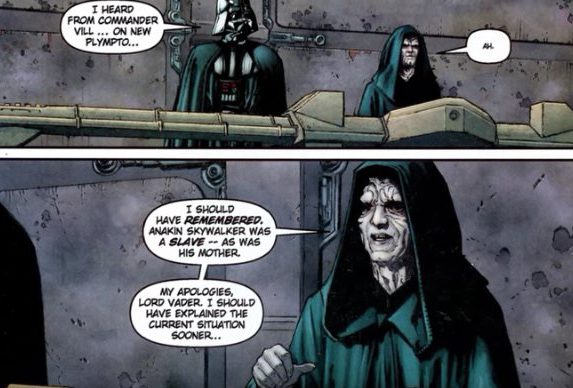

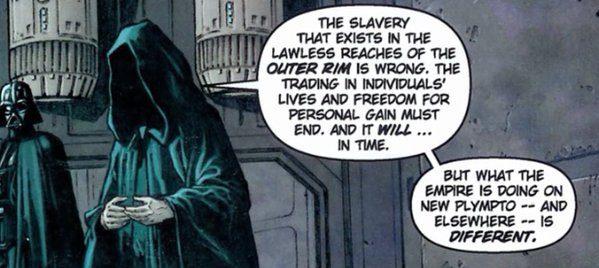

There is no longer any threat on the horizon, and there won’t be any for the next 20 years. The Clone Wars, during which he was forced to kill throughout his youth as a Jedi, are finally behind him. He even proposes an alliance with his son Luke, saying, “We can end this destructive conflict and restore order to the galaxy.” And he probably truly believes it: Anakin was born a slave, his mother died in slavery, and he grew up as a Jedi, continuously witnessing (and even participating in) the horrors of war. As Darth Vader, he intends to enforce the laws of the Empire and end war and slavery, and ultimately, he justifies his role with a specific moral vision. There are examples of Vader not sleeping at night and confronting Palpatine when he discovers a slave trade tolerated (if not managed) by the Empire on the outer rim

In the original trilogy as well, Vader’s actions are extreme but not for the sake of cruelty: he assassinates two Imperial commanders by strangling them because they are considered incompetent due to their failures, but he will never strangle Admiral Piett, who, despite failing, had followed Vader’s directives or acted sensibly.

Vader, beyond commanding the 501st Legion, is not officially part of the Imperial chain of command (we can see him more as a sort of secret agent) and may, therefore, not even have the power to remove an incompetent officer without physically “removing” him, that is, killing him. The most ruthless action against the enemy that we see in the span of three films is perhaps the strangulation of a prisoner of war at the beginning of Episode IV while he is interrogating the rebel, who seems to be killed by the process.

For twenty years, Vader’s sole objective is to become more potent than his Sith master and defeat him. During these twenty years, Palpatine tortures him. Even Vader’s suit is designed to keep him in constant physical pain, a permanent via Crucis, with the alleged intention of increasing his power of the dark side.

The suffering of the Christian messiah is nothing compared to that of Anakin. Christ endures physical torture, but Anakin has a lifetime of torture, not only physical but also psychological: he must constantly live with the weight of his actions and his failures. While Jesus takes on all the world’s sins and suffers as if they were his sins, Anakin commits the worst sins and must live with them.

The paradox is that the hatred that drives Vader is all towards his master, the ultimate authoritarian political authority, who controls everything in the lives of the Empire’s citizens and Vader’s life in his hands—an indispensable Leviathan. But Vader also needs his master both to become stronger and to survive. Without Palpatine, no one can watch over Vader during his rest, as he is forced to soak in the bacta tank to regenerate his buttocks burned by lava or to recharge the batteries of his “onesie” before going out to mow down rebels.

As a Sith, Vader is exceptionally vulnerable. The Rule of Two – one apprentice, one master – aims to prevent genocides, as the goal of a Sith is always to become the strongest by prevailing over other Sith.

But Vader, as a Sith, is terribly vulnerable, given his condition as a half-infirm. Darth Plagueis was killed in his sleep after getting drunk. If a moment of distraction was enough for Plagueis, for Vader, now dependent on Palpatine’s power, the constant need for life support means being a slave constantly at his mercy. How many around us, like Vader, depend on the Leviathan, are slaves to it, and yet cannot do without it?

Survival is not the only reason why Vader needs Sheev Palpatine. His master is the only “human” connection he has left, the only person part of his past life. He was the symbol of the Republic that Anakin, as a Jedi, defended, the symbol of the war won against the separatists that was central in Anakin’s life. He is the power Anakin served “for the greater good” before becoming Vader, and that “finally” imposed itself in the galaxy, bringing “peace.” To fight against him means to renounce much of one’s past and recognize that for one’s entire life, they have served the wrong cause. It means completely emptying one’s life of meaning. That’s why it’s so difficult to rid oneself of the Leviathan. It’s difficult to recognize the sunk-cost fallacy.

As we see very well in the series Andor, which serves as a spin-off to the excellent film Rogue One (a genuinely remarkable series for adults, unlike various Mandalorian/Ahsoka and other kiddie stuff in the franchise), good and evil are never black and white, and rebellion is undoubtedly not made up of saints. Seeing the Empire as the absolute evil is simplistic. Vader truly respects Palpatine and is somehow devoted to him, at least to his power and his ability to succeed, while Vader’s life is a constant failure.

Although he hates his master, killing him would deprive Vader of every reason to live until he encounters Luke. Despite his evil-looking suit, Vader remains a sensitive teddy bear at heart. Beyond the Great Purge at the temple, Vader is always relatively gentle with the Jedis.

For example, when facing Kanan and Ezra in the animated series Rebels, he toys with them, gently pushing them around (literally nudging them with his arms) instead of skewering them with his sword. Clearly, he spares them.

Not to mention the favoritism he shows toward his son, Luke. Vader has thirty years of combat experience and Force use, and that poor boy has taken just a few leaps with backpack Yoda, and he’s facing Vader? Bullshit.

Sure, Luke might have high midichlorian counts, but it’s not like you go into the swamp, “Do or do not, there is no try,” and bam, you become Ken Shiro. Luke realizes that his dad is a bit too soft and that if he’s not getting beaten up, it’s only because there’s some tenderness left in him (Episode VI): “I feel the good in you, the conflict…You couldn’t bring yourself to kill me before, and I don’t believe you’ll destroy me now.”

Anakin and Jesus, similarities and differences

Anakin is a more modern and darker protagonist than Jesus, and in many ways, he is much more interesting, primarily because of his humanity and psychological complexity.

Jesus accepts his defeat; he does not even consider it. It’s not a defeat; he’s too divine to perceive it as such. Anakin, on the other hand, hates it. He wants to win until the end. But in the end, he understands that, like Jesus, the real victory is in his sacrifice.

As Jesus sacrifices himself to die for us, Anakin saves his son Luke and the entire galaxy. His determination allows him to be the only being in the galaxy with the Force to move and throw away Palpatine while being struck by force lightning (determination and – well – maybe also the count in midichlorians as the chosen one helps…). Vader knowingly embraces his ultimate sacrifice because he knows his suit is vulnerable to force lightning by design. Not even Yoda can resist and move when directly hit by Palpatine (for example, in Ep. III Revenge of the Sith, in the Chancellor’s office).

In short, Jesus and Anakin are very different figures, but in some ways very similar. Let’s summarize with a table:

| Did it/Didn’t do it | Jesus | Anakin |

| Conception | Virgin Mary gives birth to him | Virgin or not, the mother is impregnated by the “Force.” |

| Paternity | as part of the Trinity, he is – also – god the father | Luke, I am your father |

| The chosen one | the messiah | the chosen one who will bring balance to the Force |

| Temptations | overcomes the temptation of the devil to turn stones into bread | is seduced by Palpatine’s dark power in the illusion of being able to save Padmé from death |

| Life sucks | Gets beaten up big time, goes through the via crucis, and gets hung on a cross. |

|

| Sacrifice | Dies for all of us defeating evil | Dies for the entire galaxy, defeating the evil Emperor Palpatine |

| Humour | Little or nothing, at least in the non-apocryphal versions | Good sense of humor and dad jokes (4) |

| Redemption | None needed; he was already perfect. But redeems all the sins of the world. | Love and admiration for his son redeems him. And frees himself from all the sins he has committed |

| Resurrection | He leaves the tomb and ascends to heaven. | Ascends to the “heaven” as an immortal Force ghost. |

Anakin Skywalker has lived so much evil that he became evil himself. He made mistakes. But he never gave up. He always fought, at least for himself. Anakin represents the indomitable struggle of the wounded and chained beast against oppressive circumstances. The oppressed individual is against the totalitarian tyranny of an overwhelming coercive force, both outside and within.

Anakin and Vader are perpetually defeated but never accept defeat and will always fight. In defeat, he lost his way and committed atrocities, but even when it seemed too late, a spark of love – the rediscovered fruit of his beloved’s womb – was enough to illuminate him and make him find his way again, sacrificing himself for a just cause.

Anakin is a realistic, pragmatic hero who makes choices and mistakes but is always a protagonist. He is never a pawn. Not even when serving Palpatine. Vader always has other plans. He represents the glorification of the individual who, despite the most significant adversity, can ultimately determine his destiny, first fighting his own Order and then winning the greatest battle, that of the dark side within himself.

Anakin is rebellious, determined, autonomous, independent, and an indomitable warrior. An icon of self-determination and passion. He is the individual against the status quo, against the established order, for better or for worse, against the Jedi and the Sith. If Jesus represents love, Anakin represents determination.

Today, what remains of Christianity is more the spirit of apathetic sacrifice of those who work and suffer, trusting in otherworldly salvation after death, rather than the anarchism of a rebellious Jesus against authority, who builds an independent kingdom based on love and values on this earth. It takes more of Anakin to reignite the flame of passion in the Western legacy of Christian origin.

Apocryphal portrait of progressivist kind, in which Jesus rushes to help but decides not to use the lightsaber. The little lamb will only see Salvation in a “better life.”

What is most terrifying today, in recent history, are the zombies surrounding us, pawns of a political or cultural regime. Never before, as in the pandemic farce, have we seen millions of these headless creatures, incapable of seeing, caring, or fighting for themselves, let alone for others or for what is right.

They are frightened by nothing, pieces of flesh spending their lives on the couch, distracted by gossip about scapegoats being shamed on TV. Apathetic pawns who don’t even claim to see a bit of sun or feel love, to feel good. Depressed zombies with Stockholm syndrome devote themselves to improbable deities like the State, collectively singing from the windows, with their masks not even lowered, the stifled Anthem of an acritical and deceased people who praise their executioner. Without passion, ideals, or determination, people who passively undergo everything are never protagonists and are afraid to act because acting can mean making mistakes, disappointing someone they know, or losing what little they have, which certainly isn’t dignity.

But history belongs only to the protagonists, for better or for worse. If you must be a monster to someone, be their Darth Vader. Make mistakes, but never stop having passion, never stop fighting. Humanity progresses only because there are those who have the courage and determination to seek the truth, even at the cost of disappointing everyone else.

Satoshi, the hidden hero

Can a hero remain eternally in the shadows, disappear, and abandon us, leaving us at the mercy of evil? Lemà sabactàni!

Like Jesus and Anakin, Satoshi is equally intangible, although he is the only one who could still be here today, walking among us. Some of us might have spoken to him or at least corresponded with him.

Yet he completely relinquished his flesh, translating himself into an inaccurate and incomplete piece of software, leaving us alone to face the world. His legacy is a community of isolated, scattered, and unorganized individuals. But equipped with the right weapons: a code, a mission, an ideal, and the keys to a secret and impenetrable kingdom, uncontrollable but accessible to anyone who wants to be part of it.

The struggle in the shadows, the distributed power

Satoshi’s complete incorporeality, as with Bitcoin, is his superpower. Satoshi can transform into an ideal and grow within us.

Like Jesus, Satoshi finds fertile ground for his message because his vision is moral. Like Anakin, he is determined to fight the status quo, the established order. Bitcoin challenges all the traditions of the last century: the overpowering role of the State, mainstream economic and monetary theory, political theory and public law, and the major social doctrines.

However, be cautious because the battle should not be tackled head-on or fought in open fields. And not because Satoshi is a coward. Satoshi remains in the shadows, the hidden hero because he is wise and cunning. Like Jesus, he knows how to confront the Leviathan. You don’t take down US Navy aircraft carriers with rifles, but in certain circumstances, you can confront the world’s most powerful army with the cost-effectiveness and practicality of the Kalashnikov. The AK-47 in poor territories like Afghanistan or Vietnam made tribes of farmers and shepherds uncontrollable by professional armies (I’m freely borrowing from “Bitcoin is a weapon” here).

A single bomb can cost the Leviathan $25,000 – not counting the cost of the aircraft carrying it, personnel, and centrally made strategic decisions to use them.

Yet a locally-produced Kalashnikov costs $150 to the shepherd who wields it. And when it’s fired at you, you’re no less dead than when a $25,000 bomb explodes in your face.

This is the true power of a distributed, economical, and inclusive tool: what is cheap and scalable can defeat what is expensive and centralized.

Thanks to cryptography, certain mathematical problems are difficult and costly to solve but easy to verify. Therefore, transferring information is possible at a negligible cost and without the possibility of being controlled. Among this information is transactional monetary data.

It’s the same “scalability” as a shepherd wielding a rifle. This is how Bitcoin allows opting out of the follies of the “fiat money” world, to which I have dedicated at least two important articles: “The Birth of Fiat Money” and “The Tragedy of Fiat Money“.

Exchanges and trade are the primary expressions of our humanity, representing evolution and progress and the primary source of wealth. Wealth attracts parasites. Political authority, by its nature, driven by the incentives that critical political actors have during their mandates, seeks to extend its influence by controlling exchanges.

The U.S. Navy controls the sea lanes of goods, while other American institutions strive to expand their control by spreading the dollar across much of the globe, establishing their standards and currency as the primary means of exchange.

The World Bank and the IMF are the spearheads of this system. Politicians from poorer countries vie to incur debt with funds provided by these institutions, enjoying all the privileges of a credit flood. The funds are tied to a centrally planned scheme prone to failure, both because they are wasted on a large unproductive bureaucratic apparatus and for reasons easily explained by Nobel laureate F.V. Hayek’s theory of “price as information”: the central planner does not know the productive dynamics of market agents and will never be able to top-down alter the long-term productivity of a people or land through funding to the public sector.

When the funds run out, and the politicians and bureaucrats who obtained the funding retire to private life, only a dollar debt remains for the population to repay to the institutions that provided the credit.

In this way, the debtor nation is forced to use the creditor’s currency. In banknotes alone, it is estimated that around 950 billion dollars are circulating outside the United States, accounting for 45% of the total. This gives the United States the power to dilute the effects of inflation: when the Federal Reserve prints new money by extending credit to the U.S. Treasury, to major financial institutions, or to big corporations (5), the newly printed money erodes the purchasing power of all dollar holders, as the effect is spread across all circulating dollars, even abroad.

However, only U.S. institutions benefit from seigniorage income. The power of money printing thus not only entails a considerable redistribution of wealth from the private sector to the public sector but even from one country to another.

Satoshi has built for humanity a silent weapon that allows us, as individuals, to take back control of our lives and, as people, to emancipate ourselves from an oppressive system. Jesus’ teaching to the Pharisees in the temple is a distant echo that resonates in Satoshi’s strategy: give Caesar what is Caesar’s and God what is God’s.

We don’t have to fight the dollar or the euro; we just need not to give a damn:

“Bitcoin doesn’t care.” Caesar is not our God. We are not his slaves, and even if we are surrounded by slaves who want to dress us up in the BDSM romper they wear so proudly. We won’t remain slaves of the Emperor, if we find the determination and motivation to fight because when we are together, our Force makes us immune to force lightning and inflation. Let’s pay back the slaver’s coin in his currency, a symbol of violence, but let’s keep the only currency that matters, a symbol of peace: Bitcoin.

You can’t control an armed nation. Nazi Germany banned weapons for civilians, and every dictatorship disarms its citizens before it can establish itself. But Bitcoin is a weapon for every home. No totalitarian regime can resist it.

Every day, a new individual wakes up from apathy; a Bitcoiner sees the light and chooses to blend into the shadows. A silent, unstoppable mass that grows until the meeting between supply and demand marks a point of no return: Bitcoin will become the balance needle of global wealth.

As of today (March 2024 at the time of writing), Bitcoin is used for settlement transactions via the blockchain only (excluding all transactions within intermediary systems, payment processors, banks/exchanges, and custodians), totaling approximately $10 billion worth of value per day. This amounts to trillions annually on-chain alone.

However, we do not commonly see Bitcoin being used for daily transactions beyond certain regions or cities. This is because of a fundamental economic law – Gresham’s Law – which states that bad money will drive out good money when mandated by state decree. Those who hold Bitcoin do not want to part with it. They dispose of bad money first and only spend the good money when nothing else is available. Therefore, the Dollar and Euro will remain in circulation for a long time as bad money because people are compelled to hold them, as demanded by authority through mandatory taxation.

Today, inflation allows public debt to be continuously renewed by printing currency that repays old debt with new debt. The issuance of new money is exponential. However, the inflationary spiral of fiat currencies leads to the system’s self-destruction, the apocalypse where all debts are forgiven to all debtors.

When fiat currency, due to inflation, becomes worthless, credits and debts lose their value. It’s a Fight Club-like happy ending, with the collapse of the credit institutions’ buildings, but where the great reset is peaceful and meritocratic.

In the presence of a concrete monetary alternative, it’s no longer like the Weimar of the 1930s, where the people’s wealth is destroyed. Inflation will no longer affect the emancipated people because Bitcoin is both a weapon and a shield for every household. It will only destroy the State that lives off that inflation, leaving more space for civil society and individual initiative.

Removing the all-powerful inflationary scepter, the Leviathan is left with only taxation and direct confiscation to redistribute value from the wealth producers of the country, namely the private sector of workers and entrepreneurs, to the parasitic class. And even against such state theft, Bitcoin offers an accessible shelter: with the speed of a click (but even without the need to click), it’s possible to move everything to the least authoritarian and oppressive jurisdiction.

Thus, it elects as its domicile, whether just financial or also physical, that jurisdiction that has earned the right to shine with your wealth. Only through the free market can a Garden of Eden arise amidst fiscal hells, and Bitcoin allows anyone to participate in this mission or at least escape from hell when the flames become too intense.

Jesus Christ anticipated two millennia the answer to the solution of the evil reigning on earth, the infinite coercive power of government through inflation. The solution is “fuck the system” or “hack the system,” it doesn’t matter much.

So here I reveal the answer to the question that has tormented you for years: who is Satoshi? It’s clear that Satoshi Nakamoto is not Adam Back or Nick Szabo, or Hal Finney or Dave Kleiman. Instead, it’s the powerful digi-evolution of Jesus Christ in the form of a force-ghost Skywalker’s apprentice digitizing himself in our era.

(Just kidding – the serious answer is in the next chapter.)

A new philosophy and aesthetics

Satoshi’s decision to hide and disappear is mythological. He has built a true epic of the Bitcoiner.

After all, Bitcoin is nothing but a moral discourse—a nonviolent revolution pivoting on a new libertarian and anarcho-capitalist philosophy. There’s a fusion of various currents, primarily the cypherpunk movement focused on the philosophical importance of privacy and an experimental and scientific Popperian approach.

The Cypherpunk Manifesto of 1993 promotes an open society, without prejudices, where everyone is free to express themselves. Therefore, every idea can be subjected to the scientific process of verification and falsifiability.

For absolute freedom of speech, privacy is necessary, as well as the ability to exchange information anonymously and uncensored. Information is not only words but also numbers, accounting, and money. If I can send you a letter freely without the blessing of the constituted power or a tyranny of the majority being able to interfere, I must also be able to send you an invoice and a payment with the same freedom. For cypherpunks, the Internet and Bitcoin are the salvation of modern culture and civilization.

Let’s consider the sanitary neo-totalitarianism of 2020: without free information via the Internet, even the most reasonable person might have been sucked into the vortex of ignorance. Or think about climarxism without Wikileaks exposing the climate-gate case and the data available on the web providing actual peer-review to the conclusions touted by the press and based on some sensational excerpt from the IPCC.

Or yet: what would we know today about Bitcoin if there were only mainstream media outlets obsessed with the sadistic and recurring kink “Bitcoin is dead” instead of various mailing lists, forums, social media, and specialized blogs where factual information can be obtained?

Human civilization has fought for centuries for the freedom of information. Despite some ongoing regressions, it is impossible mainly for an authority to isolate from knowledge a class of individuals who genuinely seek emancipation. We have made incredible strides in the struggle for freedom of information, while the fight for payment freedom has only just begun.

The cultural background of Bitcoin is nothing but the quest for a more beautiful, serene, and free world. Perhaps the most genuine form of love for one’s neighbor that a band of introverted nerds can express is the enthusiasm and palpable joy felt within the community, which is love for life and humanity.

After Erick Hughes’s manifesto, there were the first intersections with the Austrian School of Economics thanks to Nick Szabo, the first among the cypherpunks to mention the Austrian economist Menger in his paper The Origins of Money (2002).

The Austrian School of Economics, although originating in the second half of the 19th century, truly matured, in my opinion, only from the early 1990s with Huerta De Soto. These currents have in common the centrality of the individual from both an economic (from the marginalist school) and philosophical (free expression, critical thinking) standpoint and intersect with the libertarianism of early Nozick and Rothbard, representatives of economic and philosophical evolutions of classical liberalism that pass through Hayek and Mises.

The movement that gave rise to Bitcoin developed a whole series of moral precepts and ideals that have extremely practical implications (for example, “Don’t trust, verify,” which evokes the scientific and critical approach brought to the extreme, “adversarial” as it is called in jargon), but also a series of sectarian ethical and aesthetic suggestions: hodl, dyor, weak hands, no-coiner, maximalists, shitcoin, the honey badger, the “fiat-anything” series like “fiat world,” “fiat food,” “fiat government,” etc.

All the aesthetics of Bitcoin lead back to its intrinsic morality, which, with a bit of self-irony becomes an almost-religion. The many pseudo-religious references in the community are nothing more than a glimpse of the evocative power of Bitcoin’s founding ideals. This article you are reading — with tones reminiscent of an American New Age prophet – has a more deontological character than descriptive or historical.

I describe not what it is but how it should be. Or how you should be as a modern man. For just 300 euros, you can also have the version on stone tablets.

And it’s nothing compared to the “Book of Satoshi,” with its vaguely biblical and hagiographic flavor, that is, the collection of all Satoshi’s writings online, including some private messages to peers (in short, a collection of letters).

Or even the “anti-fiat religion” of Saifedean Ammous, which very trenchantly attributes even contemporary art to “corruption” due to the distortion of time preferences caused by fiat money. Up to groups like the Italian “Priory,” presided over by the esteemed High Prior, Giacomo Zucco, and his dark and mysterious cousin he always refers to when talking of known people avoiding taxes with Bitcoin (sorry, only Italian here).

Rare snapshot where Jesus is paparazzied as he bestows upon the world Giacomo Zucco as the new prophet (you can recognize Giacomo by his blue eyes).

We can laugh about it, but the aesthetic charge of the Bitcoin movement should not be underestimated.

There are individuals who are not afraid of social stigma, who seek the truth and express it, who are always independent and have the maximum autonomy of judgment. Just as Jesus died alone and abandoned, facing a wicked world, the prophets of Bitcoin are not afraid to confront the whole world by proclaiming their truth. We know we are doing the right thing, regardless of the outcome, and we fight with the same determination as Anakin.

But with the exception of the prophets and heroes, the rest of the movement is made up of many, some strong and others less so. Some need symbols, emotions, and renewed motivations to rediscover the taste for beauty. Here comes the role of the aesthetics. Find determination when everything else collapses, Padmé dies, and evil reigns supreme. Rediscover your optimism because even when defeated or seen as monsters by the rest of humanity, you are the ones doing good.

You are the heroes. You are Satoshi.

Conclusion: Rediscovering Beauty

The greater the extent of political power and bureaucratic machinery compared to the autonomy and independence of individuals, the worse the crimes against humanity we witness.

Technological, civil, institutional, and moral progress occurs in civilizations that ensure long-term peace within their borders, allowing for a thriving civil society. Historically, this peace has sometimes been achieved thanks to organized and powerful governments like ancient Rome.

However, when this power becomes too invasive and pervasive, the individual becomes a mere insignificant pawn, a servant, or worse, cannon fodder. When individuals no longer have defenses against extortion, seizures, and armed robberies like taxation, power corrupts everything, draining every resource until it destroys itself.

By monopolizing currency issuance, emperors behave like gods, from Palpatine to ancient Rome, increasingly suffocating civil society.

Today, state decisions and the outcome of the “democratic” process are unappealable divine dictates, determining how you are treated, what substances you take, how and when you leave your home, how to breathe, what distance to maintain from others, what you can or cannot touch, the tribute you must pay to the authorities even on a donation, how much money you can hold or move and in what form, what is fake news, how to keep accounts and therefore what form of writing is allowed and what is not, what your children must learn at school, what is moral and what is immoral.

When individuals’ reasoning is replaced by positive law, which permeates every aspect, every minutia of human relations, man is deprived of his humanity, becoming a robot that must follow the manual. Discussion, dialogue, critical thinking, and progress come to an end.

Moral conflict has always been one of the elements that characterized human history and is central to the progress of civilization and our humanity. Moreover, the theme of morality is one of the deepest and most beautiful, even at an aesthetic and artistic level. Suffocating means taking away our creativity, imagination, and power.

Timeless artistic works not only include great battles, intricate plots, and twists but, above all, moral dilemmas, inner conflicts, and difficult choices, which we empathize with and which make us think about our experiences and the idea of justice.

Since Sophocles’ Antigone, the principles of the family are against divine ethics, the family is against the State, and individual morality is against group ethics. Our time is marked by contemporary heroes, real or imaginary, even at the artistic, literary, and cinematographic levels.

Was it right for a torn Matthew McConaughey, heading towards deep space and the unknown, to abandon his daughter forever in Interstellar, driven by a faint hope of saving humanity? Or think about Dexter’s fascinating moral journey, the inner conflict dictated by the murderous instinct that cannot be stopped but is only channeled through the moral code imparted by his father and supported by an attachment to family.

And again, how gripping is the breaking bad of Walter White, initially driven by noble purposes: tolerating a small evil for the greater good, where can it lead us in the long run? And again, in the Chimera Ant saga of Hunter Hunter, how interesting is it to investigate what morality means for a semi-divine creature like Meruem, who fascinates us with his character development after meeting Komugi?

We are shaken by the immense tension in the protagonists of Black Sails between the libertarian and rebellious life, full of ideals and adventures, in contrast to the more pragmatic and realistic convenience, driven by personal affections, which can sacrifice everything else.

There is never a single solution to all moral dilemmas. Each individual finds their solution and balance.

But one thing is sure: it is not a positive law of an abstract and impersonal entity, distant but omnipotent, that should or can determine every aspect of our life, insinuating itself into our private exchanges, telling us what is true and just.

Bitcoin promotes cooperation, and efficient exchanges facilitate the coincidence of needs and desires among different individuals, removing intermediaries and frictions as much as possible. It optimizes the use of existing resources, reducing Coase’s transaction costs and resulting in greater wealth even without an increase in output, much like apps such as Airbnb or BlaBlaCar by sharing existing and imperfectly allocated resources (the abundance of existing houses/cars that can coincide with travel plans).

By facilitating exchanges, individuals and people are pushed towards cooperation, nullifying privileges not acquired through merits. In this way, the acceptance of differences is also easier. But we are always talking about constructive tolerance, with adversarial elements, never uncritical and politically correct like a domesticated zombie.

Bitcoin puts you in play and allows you to change, experiment, discover, and travel beyond geographical and knowledge boundaries. It challenges the system’s morality, the State’s ethics, the suitability of a means of payment, and the need for established power. Bitcoin is the moral philosophy of freedom, of critical approach, of the centrality of the individual with the autonomy of judgment, which has its dignity, also thanks to a sufficient “warlike” capacity to resist a world that is becoming increasingly totalitarian.

The ethic of non-violence promoted by the exchange is so human, so rooted in our essence, both in emotional and logical processes, that, as we have seen, it is even recognizable in our animal ancestors and constitutes one of the pillars on which modern civilization has rested and all the real progress we have made as a species.

Every piece that makes up the ethics of Bitcoin is a philosophy of non-violence, love, and cooperation that is rooted in our species and recognizable in the spheres of reason, emotions, and instinct. These characteristics can make it a minimum common denominator of many currents of thought, constituting, in fact, an all-encompassing “theory of justice.”

We have a new mythology; we have new prophets. Now go and speak; be like missionaries among the pure spirit in the world. And before spreading the word or absolute truth, infect others with your curiosity and enthusiasm, love for reason, knowledge, and beauty.

– – Many thanks to Andreas E.J. Kohl for the invaluable support in the translation from Italian – –

Note

- cfr F. De Waal, Good Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong in Humans

- This conclusion might be too simplistic or only partially true. In fact, the observation of altruistic behaviors in animals is not in itself proof that these are instinctive behaviors. Animals are also capable of logical reasoning and deductions and act based on rational choices. Animals not only understand and empathize with feelings and affections, joy, sorrow, and depression but also comprehend the meaning of giving and exchange. The combined outcome of these characteristics allows animals to consciously plan mechanisms of do ut des (quid pro quo). For example, mischievous female penguins engage in prostitution for nest-building materials when they’re lacking, such as stones brought by males, while some mammals, in addition to exchanging food and objects, seem to follow moral precepts within the group. There are interesting cases studied extensively by ethologists, such as the coalition of older chimpanzees beating the clan leader to death after he committed what they deem an immorality towards a third party, or the impudent youth showing his erect penis to the clan leader’s wife, only to quickly hide it every time the chief ape passes by on patrol.I believe what certain animals lack compared to humans is only an equal level of abstraction in language and therefore in thought: although they understand words and concepts, they are not capable of elaborating complex thoughts like we do. An intelligent dog probably reaches good levels of abstraction, such as understanding the hyperuranic concept of “dog” as a representation of the abstract set of animals of its species, but it is unlikely, perhaps impossible, that it comprehends the meaning of words like “future” or “well-being” and, above all, that it grasps concepts related to associations like “well-being in the future.” That said, it’s not unbelievable that an animal’s cognitive ability allows it to consciously plan mechanisms of do ut des and become aware of the effects of its actions.

- Dooku wasn’t merely a pawn of Palpatine, but an idealist who genuinely desired a separatist rule against the perceived corruption of the Republic. In addition to liberating as many systems as possible from the Republic, Dooku’s primary objective, since he discovers that Darth Maul, Palpatine’s apprentice, killed his own apprentice Qui-Gon, is to kill Palpatine and destroy the Sith Order. To do so, he secretly trains Ventress, but when discovered by Palpatine, he is forced to betray her. Then he attempts to recruit Obi-Wan, revealing to him that a Sith Lord governs the Senate and that with Obi-Wan’s help, they can defeat him together. Dooku, much like Anakin, isn’t dogmatic and pragmatically utilizes both the light and dark sides of the Force as tools at his disposal, without making distinctions between “good” or “bad.”

- For example, the “apology accepted” line in episode V after force choking the Imperial captain, the “be careful not to choke on your aspirations” threat in Rogue One, or in RotS (novelization) when Palpatine sends Vader to the Separatist leaders, one of them says: “But Lord Sidious promised us a handsome reward!”; and Vader replies: “I am your reward. You don’t find me handsome?” and impales him. Or yet, instead of capturing Han Solo, Leia, and Chewie in episode 5, he organizes a dinner invitation with a fully set table and Boba Fett basically hidden in the closet. How much must he have laughed saying to Boba Fett “Hey, come on, hide in the closet there, we’ll give them a big surprise”?

- For example, the $500 billion from the CARES Act, meant to “save” companies like Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, or Netflix from Covid. Paradoxical, isn’t it?

Table of contents

Jesus: “The Defeated Hero”/tldr: Jesus takes a beating but doesn’t care; his message of non-violence still prevails

- The success of Jesus between instincts and reason /tldr: Jesus’s morality resonates in both our instincts and reason, making us a more beautiful and stronger humanity

- Morality as a biological heuristic shortcut /tldr: love and reciprocity, in Jesus’ message (as in a collaborative and non-violent monetary system), lead to the right choices and progress

- Conquering the world without violence /tldr: coercive power, the State, allows for the accumulation of wealth. But it’s a negative-sum, violent mechanism, a theft. Only the exchange creates real wealth.

- Jesus against Caesar/tldr: Jesus opposes taxes and imperial currency, which are systems of impoverishment. The morality against the State.

Anakin Skywalker: “The Monster Hero” /tldr: Is Anakin/Darth Vader a hero or anti-hero? He’s a messianic figure like Jesus but with notable differences

- From Anakin to Darth Vader: the story /tldr: The entire Star Wars story has important parallels to our galaxy between Palpatine and Roosevelt and Hitler and Nero. Anakin is the figure of a man enslaved by the Leviathan, struggling to break free from this dark side inside and out, falling into the sunk cost fallacy, even emotionally attached to his sadistic master. But on the other hand, unlike the “zombies” surrounding us in this galaxy, he never accepts his condition.